The Story of Zeugma: Saving a Roman Treasure on the Banks of the Euphrates

Zeugma – A Forgotten Roman Gem

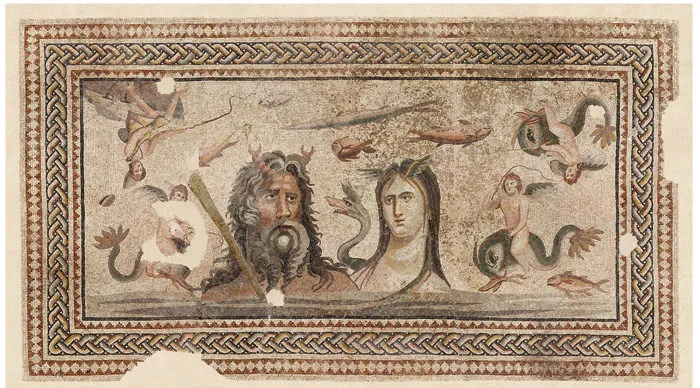

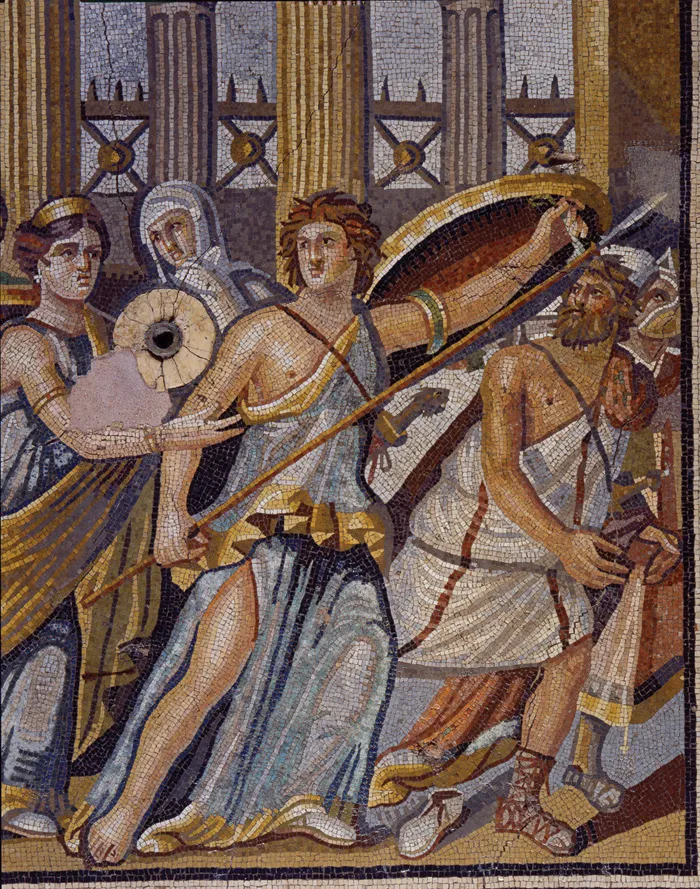

Zeugma, once a thriving Roman town, sat strategically on the banks of the Euphrates River. It served as a vital bridge connecting the Mediterranean world to Persia and beyond via the Silk Road. While its mosaics rivaled those at the Antioch Mosaic Museum and the Bardo Museum in Tunis, Zeugma’s historical richness remained deeply embedded in its landscape—until it was threatened by modern development.

A Call from Across the World: The Start of the Rescue Mission

The journey to Zeugma began unexpectedly. While on a train, I received a late-night call from a Californian philanthropist who supported our work at Butrint, Albania. He had read a New York Times front-page story warning that the ancient Roman town of Zeugma was about to be submerged by the waters of a new dam project in Turkey. The article described rapidly rising waters endangering exquisite Roman mosaics. The urgency was clear: action had to be taken immediately.

Leaving Butrint Behind: A Farewell to Albania

Before heading to Zeugma, I had to settle affairs in Albania. A planned visit from the U.S. Parks Authority, led by Brooke Shearer, was underway. Brooke, a seasoned diplomat with ties to the Clinton administration, was touring the newly formed Butrint National Park. Despite jet lag and lost luggage, she remained composed and inquisitive as we journeyed across Corfu and into Albania.

During our visit to the Roman villa excavation at Diaporit, a sudden phone call from the White House cut short our peaceful afternoon. Brooke’s nephew and godson had tragically died in an accident. She left immediately for the United States, but not before offering her support for any future work I might pursue in Turkey. That promise would soon prove pivotal.

Arrival in Turkey: From Ankara to the Edge of the Euphrates

Soon after, I arrived in Ankara, Turkey’s capital, and reunited with an old colleague, Dave K., a fellow archaeologist who had once worked briefly at Zeugma. Despite his experience and published report, Dave was wary of Turkish bureaucracy and skeptical about our chances.

Our mission was supported by Olcay, director-general of GAP, Turkey’s dam authority, and his assistant Mustafa. Together, we flew to Diyarbakır and drove through sun-scorched landscapes, past Urfa (ancient Edessa), descending into the Euphrates canyon and arriving at Birecik—the site of the dam and nearby ancient Zeugma.

Witnessing the Crisis: Zeugma on the Brink

Zeugma’s acropolis rose beyond the dam, surrounded by pistachio orchards and dry gullies. On arrival, we passed abandoned villages soon to be submerged. Some residents had been relocated to urban apartment blocks, leaving behind centuries of history and identity.

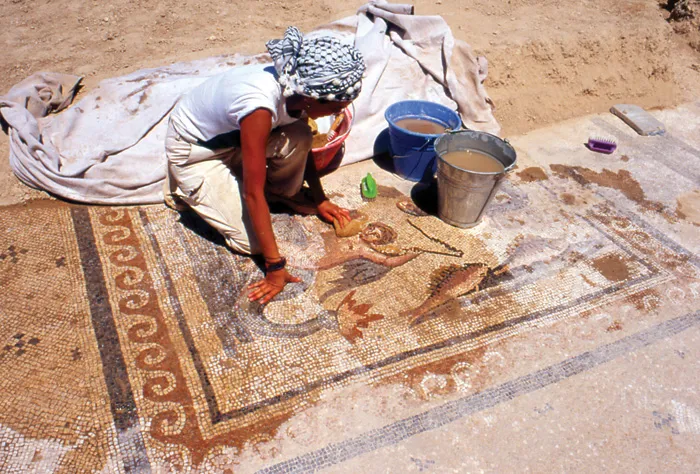

The excavation site was chaotic and crowded, more like a public spectacle than a dig. Television crews, journalists, and locals mingled around exposed Roman columns and gleaming mosaic floors. One small but determined French archaeologist—dubbed by the media as a lone guardian—was at the center of it all, working tirelessly to save the site under intense pressure.

Media Spotlight: The World Watches Zeugma

The global media transformed Zeugma into a race against time. Amid this frenzy, a stunning mosaic captured our attention. It was the work of a true master, showcasing the artistic and cultural zenith of Roman Asia Minor. The crowds included villagers whose ancestors once lived among these ruins. Their fascination and sorrow were palpable—this was not just a historical site, but part of their living heritage.

The Real Threat: Not Submersion, But Erosion

While the lower parts of Zeugma would soon be submerged and ironically preserved under still dam waters, the upper 10–20% of the site faced a greater threat: erosion. A new microclimate caused by the dam would slowly but steadily erode the shoreline. Mosaics not protected by water would be battered by wind-driven waves, gradually lost to time.

As we explored beyond the media’s reach, it became clear that the danger extended across more than a kilometer of the hillside. Untouched ruins and unknown mosaics lay buried beneath the soil, their fate hanging in the balance.

Conclusion: Zeugma’s Legacy and the Power of Serendipity

The rescue of Zeugma was never part of a grand academic plan—it was driven by serendipity, global concern, and the dedication of a small group of individuals. The summer of 2000 was a pivotal moment, when politics, media, and archaeology collided to preserve one of the Roman Empire’s eastern marvels.

While some of Zeugma’s treasures were saved, many remain hidden or lost. Yet, the story stands as a testament to what can be achieved when passion and urgency align. Zeugma today is more than a submerged city—it’s a reminder of our shared responsibility to protect the fragile threads of history.

(Image: CCA-Roma)