The Danube: Lifeline of Europe

Stretching nearly 2,000km from southern Germany to the Black Sea, the Danube has long been central to the shaping of Europe. A vital artery for trade, communication, and defense, it served for millennia as both a connector and a frontier. On my recent journey along Serbia’s middle Danube, I encountered a tapestry of archaeological riches, from Neolithic settlements to 18th-century fortresses.

Serbia Today: A First Impression

While Serbia’s recent history — particularly the turbulent 1990s during the breakup of Yugoslavia — casts a shadow, this impression quickly gives way to a more vibrant reality. Beneath the grey skyline of Belgrade lies a nation with a proud identity and deep historical roots. Serbia is a land where past and present intermingle powerfully, its story inseparable from that of Europe itself.

Novi Sad and the Petrovaradin Fortress

My tour began in the west with visits to the imperial cities of Novi Sad and Petrovaradin. Known as the “Gibraltar of the Danube,” Petrovaradin Fortress is a vast military complex built to defend against the Ottoman Turks during the Habsburg-Ottoman conflicts. The site gained fame after Prince Eugene of Savoy’s victory in 1716. Though it never saw battle again, the fortress continued to grow, with extensive underground tunnels and fortifications — expertly interpreted by local guides today.

The Roman Frontier: Danubian Provinces

Long before the Austrians, the Romans had marked the Danube as their frontier. Their conquest of the region in the 1st century BC set off wars against Illyrian and Celtic tribes. South of the river, Sirmium (modern-day Sremska Mitrovica) rose to prominence as one of the Roman Empire’s key cities. Ten emperors hailed from this city, including Aurelian, Claudius Gothicus, and Gratian. Excavations have unearthed imperial palaces, a hippodrome, and other urban features, revealing the city’s grandeur.

Vinca: Cradle of Prehistoric Europe

Heading east, I visited one of Europe’s most significant Neolithic sites — Vinca. Located on the banks of the Danube, this settlement flourished from 5700 BC to 4200 BC, housing up to 3,000 people. Vinca’s people crafted distinctive figurines, organized early agriculture, and used the river as a trade route. The site, now a large tell, contains 12 meters of layered archaeological deposits and remains a place of haunting beauty.

Lepenski Vir: Sculptors of the Mesolithic

Further east lies Lepenski Vir, hidden in the Danube Gorge. Occupied between 9500 BC and 6000 BC, this Mesolithic-Neolithic community built trapezoidal houses and created Europe’s first monumental sculptures — eerie human-fish hybrids whose purpose is still debated. The site was relocated during the construction of the Kladovo dam and now resides in a stunning glass museum, showcasing its unique contribution to European prehistory.

Roman Garrison Cities and Fortresses

Roman presence along the Danube was vast and strategic. In Belgrade (ancient Singidunum), the fortress of the IV Flavia Felix legion still survives beneath layers of later fortifications. Eastwards, at Viminacium, an enormous Roman city once hosted the VII Claudia legion. The site has yielded everything from amphitheatres and baths to the tomb of a possible emperor — and even a million-year-old mammoth skeleton, nicknamed Vika.

Entering the Iron Gates: Golubac Fortress

Approaching the dramatic Danube Gorge — known as the Iron Gates — I reached Golubac Fortress. Once a key medieval stronghold, it now marks the entrance to a region once dreaded by ancient mariners. The steep, rocky terrain rendered large Roman forts unnecessary, with only occasional watchtowers such as the one above Lepenski Vir.

Trajan’s Road and the Bridge to Dacia

It was here that the Roman Emperor Trajan undertook one of antiquity’s great engineering feats. To cross into Dacia, he had his troops carve a road into the gorge walls. Though mostly submerged due to the dam, parts of the road still exist. Just beyond Kladovo stands what remains of Trajan’s Bridge — built in AD 105 by Apollodorus of Damascus. Spanning 1,140 meters with 20 piers, it connected Rome to its new provinces. Forts protected each end, and statues likely adorned the bridge, emphasizing its imperial importance.

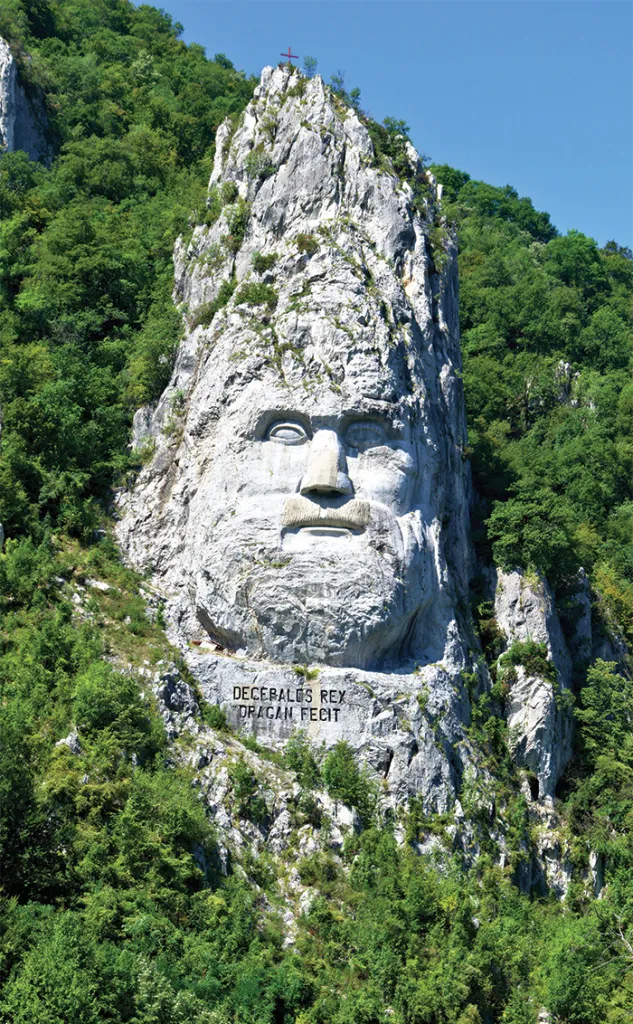

A Legacy in Stone: Decebalus and the Dacians

On the Romanian side of the gorge, a recent addition has immortalized the Dacian king Decebalus in a massive stone carving, frowning defiantly toward the south. His resistance to Rome led to Trajan’s decisive campaign, culminating in Dacia’s conquest. Today, remnants of this imperial ambition still line the hills toward the Dacian capital, Sarmizegetusa Regia.

Looking Ahead

As my journey along the Danube’s edge neared its end, I turned south. The next leg would take me deeper into the Balkans, where the ambitious architecture of Serbia’s Roman-born emperors awaits — a tale for the second part of this exploration.