Satyagraha | भारतीय स्वतंत्रता संग्राम का स्तंभ

Satyagraha

The district of Champaran is located in North Western Bihar. In British India, it was part of the Tirhut division in the provinces of Bihar and Orissa. In 1972, authorities split Champaran into the districts of Purbi (east) and Pashchim (west) Champaran. Purbi Champaran has its headquarters in Bettiah, while Pashchim Champaran’s headquarters are in Motihari.

Farmers in Champaran have been cultivating indigo since the late 1700s. In 1813, they established the first indigo industry at Bara village. By 1850, indigo had supplanted sugar as the most widely grown product in Champaran.

Tinkathia Technique

Farmers in Champaran widely used the tinkathia technique to cultivate indigo. Under this method, planters required the ryot to cultivate three kathas of indigo for each beegha of his land, or 3/20th of his total landholding (1 beegha = 20 kathas). The law did not justify this requirement; only the proprietors of the indigo factories, or planters, ordered it done.

Around 1900, European synthetic indigo began to outcompete the Bihar indigo mills, causing them to deteriorate. To avoid losses, planters started breaking their agreements with the ryots to cultivate indigo.

It asked for damages, or tawan, totaling up to Rs. 100 for each beegha to absolve the ryots of this duty. If the ryots were unable to pay in cash, planters issued handnotes and mortgage bonds with 12-percent annual interest.

Similar to Bengal, ryots in Bihar generally expressed dissatisfaction over planting indigo. They primarily resented the little payment they received for their produce. Additionally, workers at factories abused and mistreated them.

This led to two protests against the production of indigo in Champaran. Initially, in 1867, tenants of the Lalsariya factory refused to cultivate indigo. Due to the unsatisfactory resolution of their complaints, another demonstration against the tinkathia system occurred in Sathi and Bettiah in 1907–08, resulting in unrest and bloodshed.

Champaran Satyagraha

The highly combustible social and political climate of Champaran ultimately triggered the famous Champaran Satyagraha, which even Mahatma Gandhi did not anticipate. “I must admit that at the time, I had very little idea about indigo plantations and did not even know the name of Champaran, let alone its location.”

At the time, Gandhi had just returned from a successful Satyagraha against the Apartheid regime in South Africa. This experience had turned him into an emancipator.

The animosity against indigo farming forced Raj Kumar Shukla, a wealthy farmer, to convince Mahatma Gandhi to travel to Champaran and assist the downtrodden peasants.

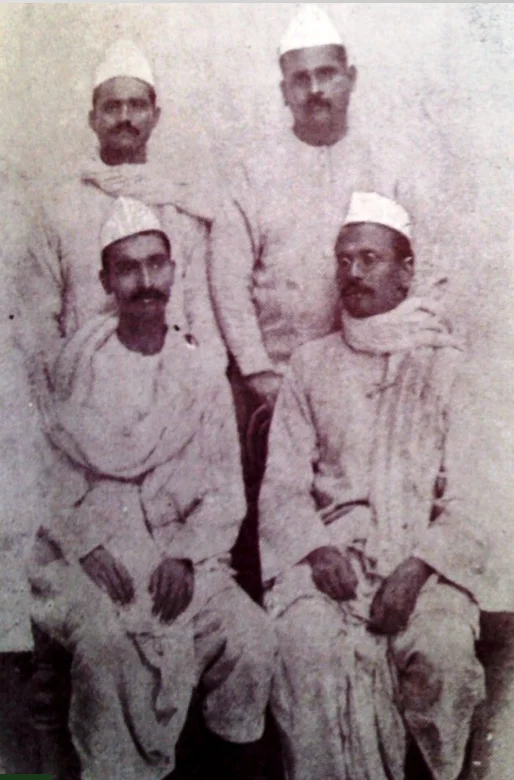

Shukla first met Gandhi at Lucknow, where Gandhi had traveled to attend the 1916 Annual Congress Meet. Shukla was accompanied by Brajkishore Prasad, a well-known Bihari lawyer who represented the tenants in court.

Initially, Gandhi did not seem impressed by either of them and made it clear that he wouldn’t take action until he personally saw the circumstances.

He asked them to approve the resolution even in his absence. During the Congress conference, Brajkishore Prasad submitted a resolution about the hardships faced by the peasants in Champaran. Shukla supported it with a speech. The members unanimously approved the resolution.

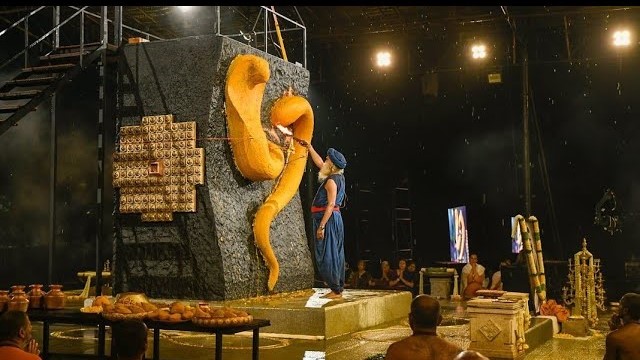

ALSO READ: Rath Yatra | भगवान जगन्नाथ की रथ यात्रा का महत्व

Britishers fears for the arrival of Gandhi

Shukla, however, was not happy. He traveled with Gandhi to Sabarmati and Kanpur. Finally, Gandhi agreed to travel to Champaran. “Come and fetch me from there; I need to be in Calcutta on such and such a date.”

The British officers were displeased to discover that Gandhi had arrived in Champaran. They feared his presence might exacerbate the already volatile situation. They also understood the need to closely monitor him and handle him cautiously due to his massive fan base.

Upon arriving in Muzaffarpur, Gandhi, understanding the circumstances, promptly sent a letter to the Tirhut Division Commissioner expressing his desire to collaborate with the administration. Additionally, he requested an appointment to explain the purpose of his visit.

At the meeting, Gandhi expressed his interest in learning more about the state of indigo production in Champaran and the complaints of the involved tenants due to public demand.

Furthermore, he stated that he had no intention of causing unrest. Ultimately, they requested him to provide his credentials as proof that the public indeed desired his coming.

Despite the explanation, British officials remained concerned about Gandhi’s intentions. They believed he aimed to incite agitation, potentially disturbing public peace. Consequently, they agreed to issue him a notice to leave the district upon his arrival in Champaran, in accordance with Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

Section 144

On April 15, 1917, Mahatma Gandhi finally arrived in Motihari, the district headquarters of Champaran. He decided to visit Jassauli, a hamlet where a tenant had suffered cruelty.

Gandhi was followed by a Sub-inspector who informed him about the issuance of an order under Section 144 and requested him to return and meet with the District Magistrate.

After his journey, Gandhi returned but disregarded the warning. He wrote to the magistrate stating his willingness to face the consequences of his disobedience and declared that he would not leave Champaran.

Gandhi was thus charged under Section 188 of the Indian Penal Code and given a trial date of April 18. One of the most significant days in Champaran’s history is the day of the trial.

A large number of ryots had gathered in front of the Court. As the trial began, the government’s attorney presented Gandhi’s case. Gandhi then delivered his remarks aloud, reaffirming his intention to avoid causing any unrest.

Instead, he expressed his desire to use government assistance to fulfill his humanitarian and national duty towards the struggling peasants. He stated his readiness to go to jail but offered no defense.

Authorities found Gandhiji’s position perplexing. They decided to postpone the sentence due to the confusion. Meanwhile, the Lieutenant Governor intervened and directed the local government to drop the lawsuit, citing insufficient evidence against Gandhi and questioning the legality of using Section 144 against him.

Additionally, he authorized Gandhi to conduct the investigation. Thus, Champaran became the birthplace of the principles of Satyagraha and Civil Disobedience, which later defined the Indian National Movement.

Indigo Cultivation Practices

Following this, Gandhiji proceeded with his investigation, starting in Bettiah and then moving to Motihari. Throughout the entire investigation, he received volunteer support from his colleagues.

Including well-known figures such as Mazharul Haq, Brajkishore Prasad, Rajendra Prasad, J.B. Kriplani, and Ramnavami Prasad. Thousands of ryots from various communities came forward to voice their complaints regarding the indigo cultivation practices. Gandhi emerged as a peasant hero amidst all this. They awaited his darshan as they considered him their savior.

The Bihar Planters’ Association fiercely objected to the investigation, claiming it painted a skewed image and might encourage ryots to attack them.

They insisted on halting Gandhi’s investigation and, if necessary, urged the government to launch its own independent investigation. Furthermore, a few European diplomats were uneasy about the situation and feared Gandhi’s investigation could escalate into an anti-European campaign.

Interview of Executive Council

As the resistance grew stronger, the government intervened. W. Maude, a member of the Executive Council of the Government of Bihar and Orissa, invited Gandhi for an interview and instructed him to submit a preliminary report on the investigation thus far.

Additionally, he advised that Gandhi should refrain from recording his associates’ statements for the time being and conduct his own discreet investigations. Gandhi submitted the report on May 13.

Nevertheless, he refused to comply with the request to forgo the services of his colleagues. “I have to admit that this request is really upsetting me. He consider it an honor to collaborate with these capable, sincere, and honorable men on the challenging tasks at hand. I believe that by abandoning them, I would also be abandoning my duty.

Over time, the government intensified its push for the creation of a Commission of Inquiry. In this context, Lieutenant Governor Sir E. A. Gait summoned Gandhi to Ranchi on June 4th to participate in a meeting regarding the drafting of a report concerning his investigation.

Committee of Inquiry Champaran’s Satyagraha

A few days later, the Lieutenant Governor in Council decided to establish a Committee of Inquiry to investigate and document Champaran’s agricultural circumstances. Gandhiji was appointed as a member of it. He discontinued personally collecting comments from the ryots as soon as the Committee was formed.

The Committee’s Resolution, outlining its responsibilities as investigating the landlord-tenant relationship, reviewing the body of prior research on the matter, and submitting a suggestion to resolve the parties’ problems, was released on June 10th.

The Committee began its work in mid-July, and three months later, on October 4, 1917, it submitted its report to the Government. Its main suggestions were as follows: First, eliminate the tinkathia system.

Second, ensure that any agreement to cultivate indigo is voluntary, with a maximum duration of three years, and made by the ryots themselves. They should also decide which land would be used for indigo cultivation. Third, return one-fourth of the tawan collected by the factories to the ryots. Fourth, cease the imposition of illicit cesses, or abwab.

Implementation to the suggestions

Nearly all of the Inquiry Committee’s recommendations were adopted by the government. A resolution was also issued to implement the suggestions.

According to this account, on November 29, 1917, W. Maude delivered a historic speech and introduced the Champaran Agrarian Bill before the Legislative Council.

The Bill was eventually passed in 1918 and became the Champaran Agrarian Act. In his autobiography, Gandhi stated that “the planters’ raj came to an end with the abolishment of the tinkathia system, which had been in existence for about a century.”