Sanchi Monument – भारतीय संस्कृति का अमूल्य रत्न

Sanchi Monument

Sanchi is one of India’s best-preserved and researched Buddhist sites. It is located on a hilltop near Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh. It spans seventeen miles east and west and around ten miles north and south.

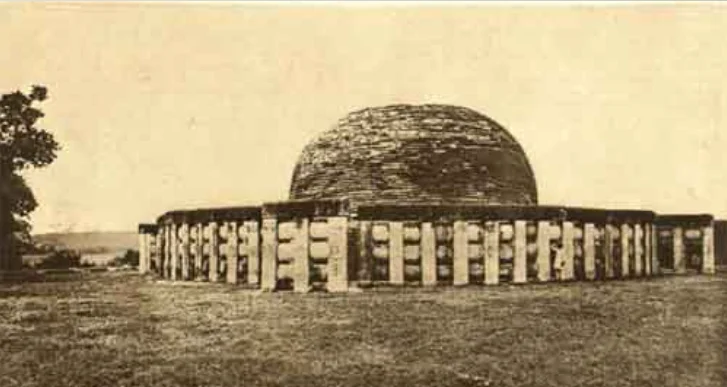

The site has multiple stupas, the most renowned of which is the Sanchi Stupa, also known as the Great Stupa. Ashoka created the Great Stupa in the 3rd century BC. It houses sacred relics or the bones of the Buddha and his most devoted disciples.

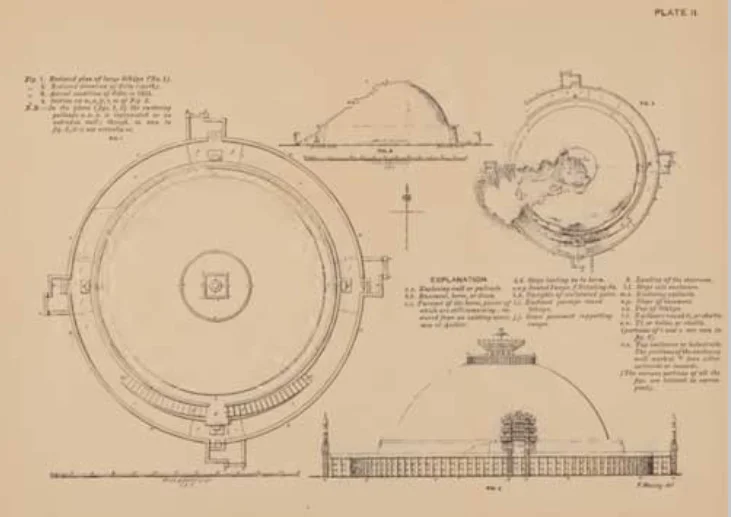

The stupa’s mound was created during Ashoka’s period. Over the following thirteen centuries, the stupa continued to expand. During the Shunga era in the mid-second century BC, the original brick construction was doubled in size, and the mound was covered in sandstone slabs.

A circumambulatory path was built around the stupa, surrounded by a stone barrier known as a vedika. Circumambulation, also known as pradakhshina, is an essential ritual and devotional activity in Buddhism.

In addition, a harmika, or square structure, was erected to the stupa. The harmika is put on top of the stupa and holds a three-tiered umbrella, or chattravali, which depicts Buddhism’s three Jewels: the Buddha, the dharma (Buddhist teachings), and the sangha.

The Satavahana Era in Sanchi Monument

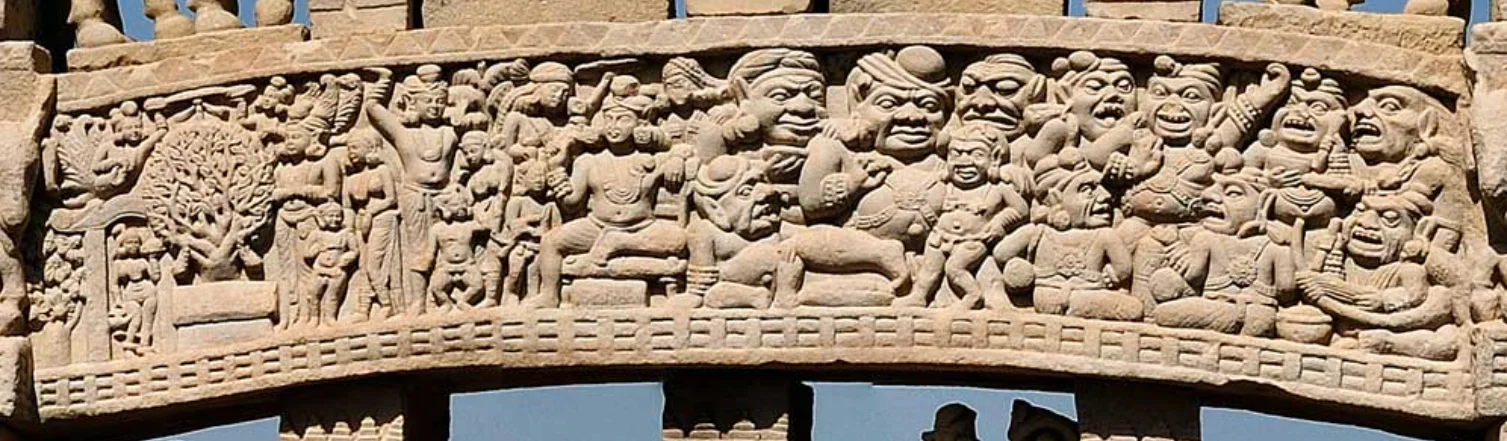

The Satavahana era, which lasted from the first century BC to the second century AD, saw the stupa’s most ornate modifications. Four stone entrances, or toranas, were erected to the stupa in the four cardinal directions.

Craftsmen made these toranas from two stone pillars topped with capitals. The capitals, in turn, support three architraves, which run from column to column and are supported by the capitals. The architraves feature volute ends and are elaborately carved with scenes from Buddha’s life and Jataka legends.

The four doorways are arranged chronologically as follows: southern, northern, eastern, and western. All of these entrances were provided by devoted people, and their names are written on the pillars.

The finely carved pillars are historically significant due to the relief sculptures on them. These numbers provide insight into the lives of individuals in the third quarter of the first century B.C.

During the Gupta dynasty, Sanchi was expanded much more. These feature a Buddhist temple and a lion pillar. The triumph inscription of Chandragupta II is carved on the railing of the Great Stupa and dates from the fourth century A.D.

People claim that the site served as a vibrant religious center from the third century BC until the twelfth century AD. Its collapse as a major religious destination corresponded with the decline of Buddhism on the Indian subcontinent.

The Great Stupa at Sanchi Monument

In 1818, the British rediscovered the Sanchi location. The Bengal Cavalry’s General Henry Taylor is credited with the rediscovery. The nearly undamaged condition of the Great Stupa at Sanchi piqued the curiosity of a rising number of explorers and amateur archaeologists, the majority of whom were army officers and traveling antiquarians.

Major Alexander Cunningham supervised the first scientific excavation of the stupa in 1851. He and his colleague, Lieutenant-Colonel F.C. Maisey, created sketches of the site.

They discovered far too many valuable finds here. Cunningham and Maisey subsequently divided the relics, and nearly all of the reliquaries were shipped to England.

Outside the Sanchi site, researchers also performed excavations at the adjacent stupas of Sonari, Satdhara, Bhojpur, and Andher, which are six and twelve kilometers from Sanchi.

Cunningham and Maisey subsequently divided the valuable finds here, and nearly all of the reliquaries were shipped to England.

Sir Robert North Collie Hamilton, the British A resident in Indore, wrote for the Govt. of India in The Committee on November 23, 1853, about a proposal made by Sikander Begum, the Begum of Bhopal, to present Queen Victoria with the carved stones of two of the Tope’s Gateways (northern and eastern) at Sanchi Kana Kheree.

Removal of the Carved stone

They began preparations to remove the beautifully carved stones of the two entrances for shipment to London. However, the cost and care necessary to demolish the edifice without ruining the delicate carvings slowed the preparations for its removal.

They suspended the evacuation due to a lack of adequate transportation to Bombay. The Rebellion of 1857 further hampered the big plans for removing and transporting these gates, plunging the British administration and the Bhopal Durbar into a volatile political scenario.

In 1868, the Begum of Bhopal reiterated her offer to give the gates to the British Museum. The colonial government rejected the begum’s offer this time because it was committed to implementing an in-situ preservation and monument protection policy.

Instead, in 1869, Lieutenant Henry H. Cole of the Royal Engineers prepared a plaster cast of the eastern gateway, which he then shipped to London’s South Kensington Museum.

It was a large-scale effort that entailed recruiting Royal Engineers and training them in the production of gelatine casts, piece moulds, and clay squeezes.

Sanchi’s Preservation & Conservation

In 1869, H.H. Cole arrived at Sanchi, becoming a significant predecessor in the conservation and preservation efforts of the site.

Authorities undertook extensive repairs on the Sanchi monuments during that period and initiated a massive project to copy, photograph, and replicate them. From the 1880s onward, the British government in India actively worked to protect the historic site of Sanchi.

The British authorities welcomed the first phase of conservation at the site. However, this effort also caused disaster for several smaller stupas around the main stupa. Which they displaced to construct a road leading up to the main monument.

They placed the restored southern gateway’s lintels front-to-back. Fearing further damage to these structures, authorities never reversed these mistakes.

In 1904, Mr. Cook, the State Engineer, initiated the second phase of this well-meaning but misguided conservation effort at Bhopal.

The repair process damaged the pillars and coping stones of the main fence around the Great Sanchi Stupa and erased their donor names.

The irreversible deterioration of the structures sparked controversy within the administrative and archaeological communities. The Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, famously characterized these actions as the “consecration of a desecration.”

Conservation of Sanchi Topes

The British Government had focused on conserving and maintaining the Sanchi Topes. When Lord Curzon made his first visit to Sanchi in 1899, he developed a keen interest in its preservation. While traveling to Bhopal in November 1905.

He suggested handing over the Topes to the Indian government. Sultan Jahan, the Begum of Bhopal, declined and asserted that the Bhopal State would preserve the Buddhist complex as a historically significant landmark. She formulated plans for the preservation and repair of Sanchi.

Between 1912 and 1919, John Marshall, the Director General of Archaeology in India. Carried out the third stage of the restoration project at the Sanchi site, sponsored by the Bhopal state.

During this period, Marshall worked on repairing the extensive damage that had left the majority of the stupas at the location in ruins. He established a modest on-site museum at the base of the hill. Dedicated to preserving and maintaining the artifacts scattered around the site.

ALSO READ: Diamond of Destiny: The Kohinoor Story

The Begum of Bhopal fully funded the construction of this museum, with complete assistance provided by the Bhopal Durbar.

The Sanchi caskets’ return

In 1920, Nawabzada Hamidullah Khan, the heir apparent to the Bhopal Durbar, wrote to Lieutenant Colonel C.E. Luard, the Political Agent at Bhopal.

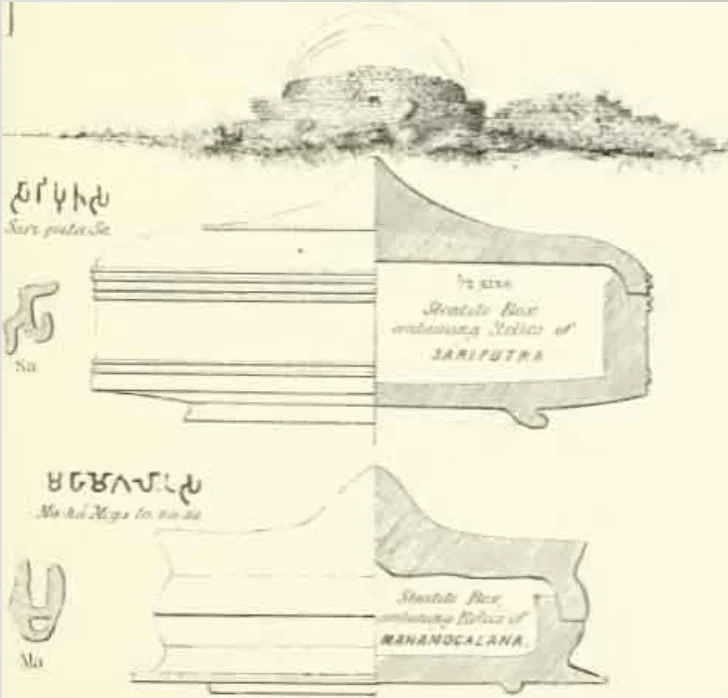

Alerting him to certain relic caskets and other items that Alexander Cunningham had removed from Sanchi and taken to the British Museum.

He asserted that Sanchi had its own museum and claimed entitlement to these priceless items, requesting their return. Alongside the letter, he included a 1919 list of seventeen Sanchi objects that John Marshall had compiled and submitted to the British Museum.

Marshall responded to Luard’s referral of the restoration of the Sanchi antiquities by stating that the British Museum would not consider returning the original antiquities to Sanchi.

He also warned that establishing such a precedent would quickly lead the British Museum to face demands from Greece, Egypt, Italy, and many other countries for the return of half its treasures. Marshall urged the Political Agent to drop the matter.

The issue resurfaced in 1940 when people renewed their demand to restore the artifacts to the Sanchi Monument. According to the Press, the Victoria and Albert Museum planned to give the remains of Sariputra and Moggallana. The two main disciples of Buddha, to the Maha Bodhi Society for housing in the Buddhist Temple in New Delhi.

Maha Bodhi Society

In 1938, the Maha Bodhi Society of Bombay requested that the Government of India retrieve the relics of Sariputra and Moggallana from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Following intervention by the Secretary of State for India. The Museum agreed in 1939 to release the relics to the Maha Bodhi Society. However, the outbreak of World War II forced a postponement of the relocation of the artifacts.

The war’s involvement proved timely for the Bhopal Durbar. L.G. Wallis, the Political Agent in Bhopal, received a letter from the Bhopal Durbar reiterating their demand for the antiquities.

The letter asserted that the relics belonged to the Government of Bhopal. And insisted that they restore them to the Sanchi Museum, considered the most suitable location for them.

Struggle for the pilgrim

They ceaselessly struggled to retrieve the relics and return them to the Sanchi Monument. They prepared to accommodate the relics in a way that respected the religious needs of Buddhist pilgrims. The Government of India requested the Bhopal Government to persuade the Mahabodhi Society to place the relics in a temple in Sanchi Monument.

As a result, in 1946, the Maha Bodhi Society and the Government of Bhopal reached an agreement to house the relics at a newly constructed vihara in Sanchi.

On November 30, 1952, they finally placed the relics, still in their original caskets. At the newly built Chetiyagiri Vihara in Sanchi. The inauguration of Sanchi Monument as a national monument took place in a grand ceremony attended by international dignitaries. Buddhist leaders from Burma, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India.