The Mystery of the Lion Man Figurine

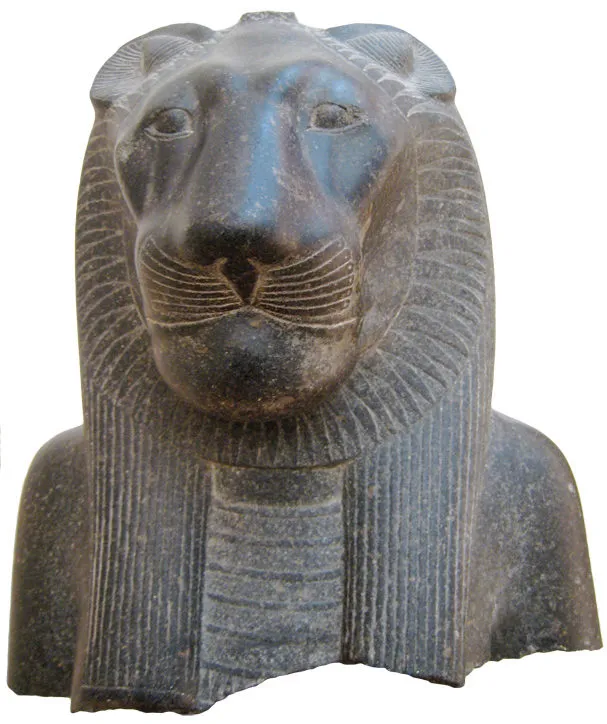

The enigmatic Ice Age figurine known as the ‘Lion Man’ has captivated archaeologists and the public alike since its discovery in 1939 in Hohlenstein-Stadel cave, south-west Germany. Frequently hailed as the oldest known representational artwork in human history, the sculpture has been interpreted as a shamanic symbol, or even the first depiction of a deity. However, recent research challenges these interpretations, suggesting a more grounded and plausible explanation.

ALSO READ: The Sumerian Plaque: A Rare Glimpse into Early Dynastic Art and Ritual

Discovery and Initial Reconstruction Efforts

Unearthed on the Eve of War

The Lion Man’s story begins in 1939 when geologist Otto Völzing uncovered hundreds of ivory fragments in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave. With the outbreak of World War II imminent, excavation efforts were abruptly halted. The fragments lay forgotten until 1969, when Joachim Hahn rediscovered and partially reconstructed them using UHU glue. This first assembly involved around 200 of the 260 fragments.

Reconstructing a Puzzle from Fragile Ivory

The original reconstruction was far from definitive. The ivory’s flaking surface and uncertainty about fragment placement meant the figurine’s upper body—especially the head—remained speculative. Hahn initially hesitated between identifying the head as that of a bear or a feline. Subsequent work in 1982 by Elisabeth Schmid added new pieces and led to the definitive identification of the head as a lion’s.

Later Restoration and Ongoing Challenges

A Tedious, Fragile Restoration Process

A more detailed restoration was conducted between 1987 and 1988. Conservator Ute Wolf meticulously reassembled about 250 fragments using advanced conservation techniques. Nevertheless, significant portions of the figurine, especially the head, had to be reconstructed with wax and chalk, making parts of the sculpture more speculative than authentic.

New Fragments and Mounting Complexity

Between 2009 and 2013, archaeologists recovered 575 additional small fragments. After analysis, 139 were identified as bone or antler, not ivory. Some of these pieces were incorporated, but many remain unmatched. Experts now suggest the possibility that multiple carvings may have existed at the site, compounding the uncertainty of the figurine’s true form.

The Lion Man Debate: Feline or Ursine?

The Lion Interpretation: Popular but Questionable

Supporters of the lion hypothesis compare the figurine’s head to lion depictions found at Vogelherd and Kostenki. However, these comparisons reveal significant anatomical differences. The figurine lacks lion-specific features such as whiskers, prominent teeth, or a tail. Moreover, Ice Age cave lions were likely maneless, removing another key identifying trait.

Bear-Like Features Suggest an Alternative View

Critics argue that the body resembles a standing bear more than a human or a lion. Bears frequently stand upright, a behavior not typical of lions. Anatomically, bear joints—especially knees and ankles—closely resemble human ones, further blurring the line between human and animal in artistic representations.

The broad snout in the most recent reconstruction aligns more with a bear than a lion. Observers have even likened the snout to that of Baloo from Disney’s The Jungle Book—hardly leonine.

Why a Bear Makes More Sense

Bears in Ice Age Culture

Bears held significant symbolic and practical roles in Ice Age societies:

-

Anatomical Similarities: Bears and humans share comparable skeletal structures and footprints.

-

Behavioral Parallels: Bears give birth, breastfeed, and live in caves—habits familiar to human groups.

-

Spiritual Significance: Bear teeth and claws were often removed and worn as pendants, possibly as talismans or ritual items.

-

Mythological Resonance: The idea of a creature hibernating and then reawakening may have held powerful symbolic meaning.

A Better Cultural Fit

Given the importance of bears in Ice Age life, it’s more plausible that the figurine represents a bear, either naturalistic or anthropomorphic. The upright posture, lack of definitive lion features, and cultural reverence for bears all point to this interpretation as more grounded in reality than the more exotic ideas of gods or shamans.

Conclusion: Reconsidering the Lion Man’s Identity

The popular vision of the Lion Man as a divine or shamanic figure may be more fantasy than fact. The evidence increasingly suggests that this iconic sculpture is not a lion-headed god or an early spiritual being, but a stylized representation of a bear, an animal of immense importance to Ice Age humans.

As fascinating as interpretations involving gods or spirits may be, it is crucial to base archaeological conclusions on physical evidence and cultural context. The ‘Lion Man’ may not be a god—but in its own way, as a symbol of the deep connection between humans and nature, it is no less magnificent.