The Significance of Palmyra’s Funerary Sculptures

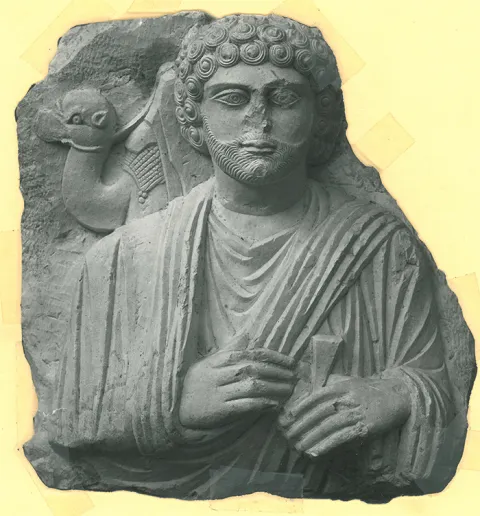

What can an extraordinary group of sculptures commemorating the dead reveal about ancient life in Palmyra? Thousands of ancient inhabitants’ portraits once adorned lavish family tombs in cemeteries just beyond the desert city. Studying these artistic masterpieces provides valuable insights into wealth, power, family dynamics, and the balance between local traditions and outside influences in this major trading hub. As researchers Eva Mortensen and Rubina Raja reveal, these funerary portraits offer a window into the unique cultural identity of the Palmyrenes.

The Ancient City of Palmyra

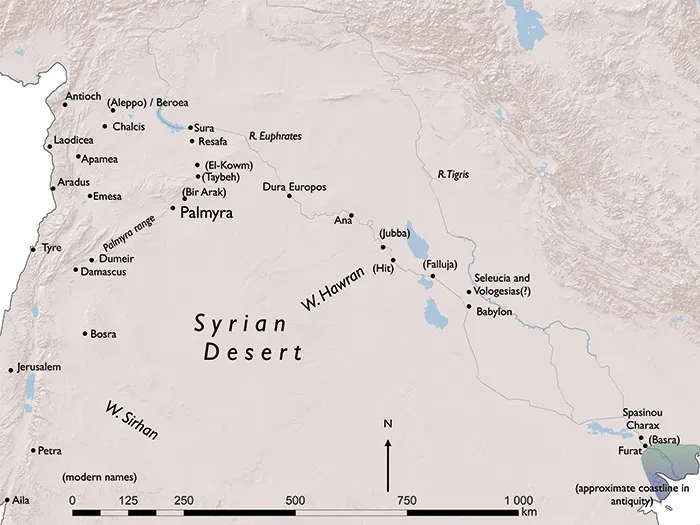

Palmyra, an ancient oasis and caravan city, lies in the middle of the Syrian Desert. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980, Palmyra has gained attention in recent years due to the destruction of its archaeological heritage during the Syrian civil war. Despite this, the city’s legacy endures, as thousands of limestone portraits of its ancient inhabitants are preserved in museums and collections worldwide.

The Palmyra Portrait Project

Since 2012, a team of researchers from Aarhus University, Denmark, has been studying these funerary portraits. These sculptures not only put a face to thousands of Palmyrenes but also reveal much about their lives and cultural traditions. The Palmyrenes inhabited an oasis surrounded by miles of desert, with long and arduous travel required to reach cities like Damascus to the west and Dura-Europos to the east. Palmyra was positioned in a border region between the Roman and Parthian empires—two major powers frequently in conflict—yet managed to maintain its distinctive identity over more than 300 years of Roman rule.

A Flourishing Trade Hub

Palmyra thrived as a crucial trading hub, facilitating commerce between the East and the West. While it was heavily involved in the camel caravan trade, its influence also extended to maritime exchange via the Euphrates, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean. Exposure to outside influences shaped Palmyrene culture, yet the city remained deeply rooted in its traditions. Economic fluctuations, long-term climate changes, epidemics, and political or military upheavals required adaptability to sustain prosperity. The city’s isolation also necessitated the creative use and reuse of resources.

The Urban Landscape of Palmyra

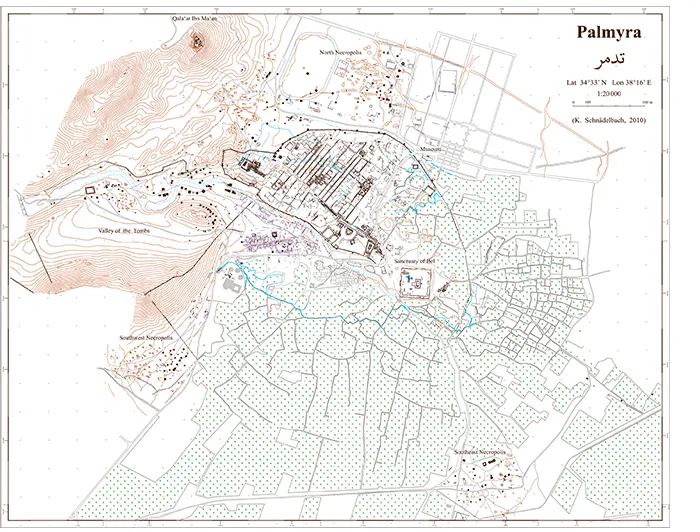

During its peak, Palmyra was adorned with magnificent architectural marvels, including:

- Temple complexes

- Broad colonnaded avenues

- A large theatre

- Bath complexes

- An agora

- A triumphal arch

Just beyond the city, four extensive necropolises served as burial grounds for the Palmyrenes. These cemeteries, located along the main access routes to the city, were among the first sights greeting both locals and foreign visitors. Caravans bustling with perfume, spices, wine, salted fish, wool, alabaster jars, and perfumed oil would frequently arrive and depart, managed by the city’s high-status merchants—many of whom were depicted in the funerary sculptures.

Palmyra Under Roman Rule and the Rise of Zenobia

Palmyra was annexed by the Roman Republic in the 60s BC during Pompey the Great’s campaign. It remained under Roman control for most of the next seven centuries, with a brief period of independence in the 3rd century AD.

Zenobia, the Palmyrene queen, led a rebellion against Rome after the assassination of her husband, Odaenath, in AD 267 or 268. As regent for their son, Vallabath, Zenobia expanded Palmyra’s territory, taking control of parts of Asia Minor and Egypt. This challenged Rome’s dominance, leading to a confrontation with Emperor Aurelian. In AD 272, Zenobia was captured, and a second Palmyrene uprising in AD 273 was brutally suppressed. Rome sacked the city, executed many of its leaders, and stripped Palmyra of its political and economic power. Following these events, much of the population dispersed to rural areas, and the city diminished in size and significance.

The Enduring Legacy of Palmyra

Despite its decline, Palmyra never faded from historical memory. Its ruins captivated western travelers during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, inspiring literature, music, and art. In the late 19th century, Palmyrene relief sculptures were transported to European museums, with the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen and the Musée du Louvre in Paris among the first to acquire large collections.

Archaeological Studies and the Palmyra Portrait Project

A major breakthrough in the study of Palmyrene funerary art came in the 1920s and ’30s when Danish archaeologist Harald Ingholt conducted research on tomb complexes near Palmyra. His comprehensive study of the iconography and chronology of portrait reliefs laid the foundation for further research.

Conclusion

The funerary sculptures of Palmyra provide a remarkable glimpse into the lives of its ancient inhabitants. As a city that balanced tradition and innovation while thriving in a challenging geopolitical landscape, Palmyra remains an extraordinary testament to resilience and cultural richness. Through ongoing research, the legacy of this desert city continues to be uncovered, ensuring that its people and their remarkable artistry are never forgotten.