Introduction: A New World Heritage Site

In July 2019, UNESCO added the Plain of Jars in Laos to its list of World Heritage Sites. Scattered across the rugged and forested landscapes of northern Laos, these clusters of 1m- to 3m-tall carved stone jars remain one of Southeast Asia’s most enigmatic archaeological phenomena. With over 100 sites now documented and many more potentially hidden beneath dense vegetation, these megaliths continue to inspire both wonder and investigation.

Origins and Early Research

The Enigmatic Creators

Although the exact origin and purpose of the jars remain unclear, they are generally attributed to an Iron Age culture (c. 500 BC–AD 500) known for increasing social and political complexity. The massive jars—sometimes appearing in solitary placements and other times in groups of several hundred—are believed to be connected to funerary practices.

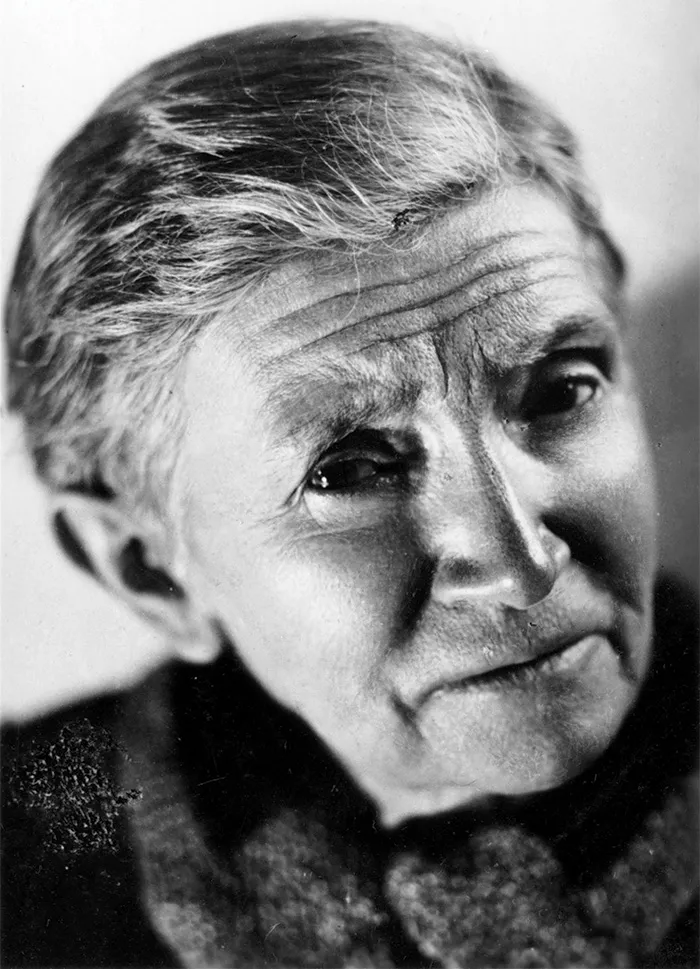

Pioneering Work by Madeleine Colani

The first significant archaeological work was undertaken by Madeleine Colani (1866–1943), a French archaeologist. In the 1930s, Colani excavated the key site now known as Ban Hai Hin (Site 1), and documented over 20 other jar sites. Her discoveries included:

- Human skeletal remains

- Ceramic vessels

- Stone and glass beads

- Iron tools and bronze ornaments

- Spindle whorls and ground-stone objects

Some jars even reportedly contained human bones and beads, though most were empty. Colani proposed that a nearby limestone cave served as a crematorium.

Challenges to Continued Research

Unexploded Ordnance and Site Access

For decades after Colani’s research, further excavation was hindered due to the presence of unexploded military ordnance, a tragic remnant of the Vietnam War. This danger made large parts of the Plain of Jars inaccessible until modern clearance efforts enabled renewed archaeological investigation.

Modern Excavations and Expanding Knowledge

1990s Renewed Research

In the 1990s, archaeologists Eiji Nitta and Thongsa Sayavongkhamdy resumed research, unearthing similar artefacts and noting new features:

- Chipped stone pavements surrounding jars

- Buried limestone slabs associated with burials

- Use of boulders as burial markers

Radiocarbon dating revealed activity spanning from 7552 BC to AD 1214, though these results raised more questions than answers.

UNESCO Surveys and Site Database

In the early 2000s, UNESCO-supported teams led by Julie Van Den Bergh and Samlane Luangaphay surveyed the region, documenting 58 GPS-located jar sites and identifying 26 more unexplored locations. Continued surveys have now brought the total to over 100 sites.

Comparative Sites in Asia

Megalithic jars are not unique to Laos. Similar sites exist in:

- Assam, Northeast India – with matching highland terrain and environment

- Central Sulawesi, Indonesia – where stone vats called kalambas resemble Laotian jars

These parallels suggest a broader Southeast Asian megalithic tradition.

Return to Site 1: Ban Hai Hin

Survey and Documentation (2016)

An international Lao–Australian team returned to Site 1 in 2016 to thoroughly document the site. Key observations:

- 316 stone jars arranged in five groups across a 30-hectare area

- Sandstone discs (20+) interspersed with the jars – possibly burial markers rather than lids

- 308 exotic boulders, interpreted as tombstones marking ceramic burial jars

- Use of drone imagery for mapping and preservation

Excavation Findings

Excavations around Group 2 jars yielded:

- 18 individuals, mostly secondary burials (disarticulated bones or remains in ceramic vessels)

- A rare primary extended burial, fully articulated

- High infant mortality, with over 60% of remains belonging to infants or unborn children

This data hints at a large mortuary population—potentially over 8,000 individuals buried near Site 1.

Isotope and Radiocarbon Analysis

- Isotope studies are ongoing to understand diet and mobility

- Radiocarbon dating from charcoal samples indicates site activity from 8200 BC to AD 1200, with most activity between the 9th and 13th centuries AD

- Only one sample (AD 1163–1125) came from beneath a jar, suggesting burials might post-date jar placement

Unanswered Questions: Transport and Placement

Quarry Origins and Movement

Recent studies show the Phukeng quarry, 8 km from Site 1, as the source of some jars. But how these 30-tonne megaliths were moved remains unclear. Theories include:

- Rolling pulley systems

- Animal-powered transport (elephants or buffalo)

Regardless of method, the effort reflects advanced logistics and coordination.

Exploring High-Altitude Sites: Site 52

A Remote Mortuary Landscape

Unlike Site 1, most jar sites are located on ridges and hill slopes. Site 52, northeast of Site 1, lies at 1,300m elevation near a Hmong village. Features include:

- 415 jars and 219 discs/boulders, grouped among dense forest

- Some discs bear zoomorphic carvings

Excavation Results

Although eight areas were excavated, very little material culture was recovered. Only a single tooth was found, likely due to acidic soil destroying bone remains. However, features like stone pavements and exotic boulders suggest the site was also funerary in function, similar to Site 1.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Archaeological Puzzle

The Plain of Jars continues to fascinate archaeologists and historians. While recent excavations have significantly advanced understanding of their funerary significance, key questions remain:

- Who created the jars?

- When exactly were they placed?

- How were they transported?

Ongoing studies involving OSL dating, geochemical sourcing, and isotope analysis aim to unravel these enduring mysteries of the Laotian highlands.