Lakshman Rekha: A Divine Boundary with Consequences

Growing up, I often heard the phrase, “Sita was also required to adhere to the Lakshman Rekha. To defy it, who are you?” This statement was frequently directed at the girls and women around me by parents and family members. It left me wondering—what exactly is this Lakshman Rekha? And why is there such an expectation for it to be strictly followed?

ALSO READ: Erakesvara Temple A Sacred Jewel

Lakshmana drew a line in the dirt, known as the Rekha. Around the jungle house he shared with his elder brother Rama and Rama’s wife, Sita. This line was meant to protect Sita while Lakshmana went in search of Rama. The story unfolds with Rama chasing a golden deer, which is actually the demon Maricha in disguise. After Rama kills the deer, Maricha transforms back into his true form and cries out in Rama’s voice, “Lakshmana, save me!” Hearing this, Sita becomes distressed and insists that Lakshmana go find his brother. Despite his reluctance, Lakshmana, unable to bear Sita’s tears, decides to leave in search of Rama.

The Lakshman Rekha: Boundaries of Protection and Societal Expectations

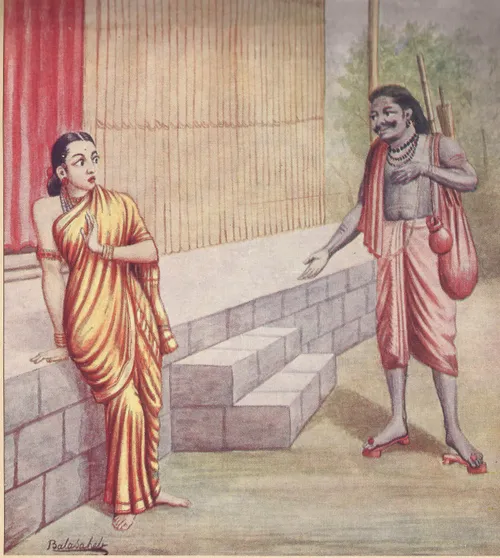

Before leaving to search for Rama, Lakshmana makes Sita promise to stay within the protective boundary he has drawn around the house. According to tradition, anyone who tried to cross the line—except for Rama, Sita, or Lakshmana—would be burned. After Lakshmana departs, Ravana, the rakshasa king, arrives disguised as a beggar and asks Sita for alms. Unaware of the deception, Sita steps outside the Lakshmana Rekha to offer him charity. The moment she crosses the line, Ravana seizes the opportunity, abducts her, and flies her to Lanka in his Pushpaka Vimana.

In modern Indian discourse, the term “Lakshmana Rekha” symbolizes a strict custom or rule that must not be violated. It often refers to moral limits or boundaries, the crossing of which could lead to adverse consequences. However, it is also commonly invoked as a way to enforce boundaries on women, urging them to adhere to societal expectations.

Sita’s Strength and Lakshmana’s Dilemma

This narrative raises several questions. Sita, the daughter of King Janaka, was trained in politics and combat just like a male heir. The concept of female warriors isn’t new to the Ramayana. Sita was a physically capable character—she was the one who lifted the Pinaka (Shiva Dhanush) in her youth. Similarly, Kaikeyi, King Dasharatha’s third wife and the princess of the Kekeya Kingdom, is celebrated for saving his life during a battle. Her bravery earned her two boons from the king, which she chose not to use immediately. Given the strength and capability of women in the epic, why did Lakshmana feel the need to draw a boundary to protect Sita?

To find an answer, I started exploring various translations of the Ramayana. My first step was to delve into the pages of the Valmiki Ramayana. While reading the Aranya Kanda, I came across these lines.

ताम् आर्त रूपाम् विमना रुदन्तीम्

सौमित्रिः आलोक्य विशाल नेत्राम् |

आश्वासयामास न चैव भर्तुः

तम् भ्रातरम् किंचित् उवाच सीता || ३-४५-३९

ततः तु सीताम् अभिवाद्य लक्ष्मणः

कृत अन्जलिः किंचिद् अभिप्रणम्य |

अवेक्षमाणो बहुशः स मैथिलीम्

जगाम रामस्य समीपम् आत्मवान् || ३-४५-४०

The translated shlokas describe how Lakshmana, observing Sita’s distressed state, tried to console her by assuring her that Rama would return soon. Despite his efforts, Sita remained silent and resentful toward her brother-in-law, refusing to speak to him at all [3-45-39]. However, with his customary respect for Sita, the self-respecting Lakshmana approached her briefly, folded his hands in reverence, and then set off to find Rama. As he departed, he repeatedly looked back, concerned for the lone woman left behind in the heart of the jungle [3-45-40].

Lakshmana’s Trust and Departure

In the Valmiki Ramayana, Lakshmana did not draw a boundary to protect Sita; instead, he simply walked away, perhaps trusting in her ability to protect herself. Similarly, these lines appear in the Ramcharitmanas, the 16th-century work by Tulsidas, which is now the most widely recognized version of the Ramayana in India.

मरम बचन जब सीता बोला। हरि प्रेरित लछिमन मन डोला॥

बन दिसि देव सौंपि सब काहू। चले जहाँ रावन ससि राहू॥3॥

The translation reads: Lakshman, influenced by Lord Ram’s divine will, decided to leave after Sita spoke harsh words to him. Understanding Sita’s concern but confident that no harm could befall the Almighty Lord Ram, he entrusted Sita’s safety to the deities of the forest and the guardians of the ten directions. He then proceeded to join Lord Ram, who was destined to be Ravana’s nemesis, just as Rahu is to the Moon during an eclipse.

Tracing the Origins of the Lakshman Rekha

In the Ramcharitmanas as well, Lakshmana did not draw a line; instead, he sought the protection of the Digpalas, the deities who govern the directions and the forest, before embarking on his journey to find Rama. So, where exactly did the concept of the Lakshman Rekha originate?

The Ramayana, an Indian Hindu epic, exists in over three hundred versions, depending on the method of counting. The earliest known version is the Sanskrit Mula Ramayana, which, according to the sage Narada, is considered the original. Valmiki, the author of the Valmiki Ramayana, is believed to have received this knowledge from Narada. Over time, various regional translations of the original Valmiki version have introduced plot twists and thematic modifications.

Some of the notable adaptations of the Ramayana include the 12th-century Tamil Ramavataram, the 12th-century Kannada Ramachandra Charitapurana or Pampa Ramayana by Nagachandra, the 13th-century Telugu Ramayanam, the 16th-century Awadhi Ramcharitmanas, the 17th-century Malayalam Ramayana, the Khmer Reamker, the Old Javanese Kakawin Ramayana, the Thai Ramakien, the Lao Phra Lak Phra Lam, and the Burmese Yama Zatdaw. These are just a few of the many regional adaptations of the classic epic.

Uncovering the Roots of the Lakshman Rekha Myth

In an attempt to trace the origins of the Lakshman Rekha myth, I consulted various researchers who have studied the many regional versions of the Ramayana and published essays and comparative analyses. Researchers have linked the myth to two specific regional versions: the Telugu Ranganatha Ramayana and the Bengali Krittivasa Ramayana. The Ranganatha Ramayana, written by the poet Ranganatha (also known as Gona Budda Reddy) between 1300 and 1310 CE, and the Krittivasa Ramayana, penned by the Bengali poet Krittibas Ojha in the 15th century, are both cited as sources for this narrative.

Understanding the chronological order of these compositions helps clarify why the Lakshman Rekha narrative was incorporated into the Ramayana. The Valmiki Ramayana was composed approximately two thousand years ago. While the precise time of its creation remains uncertain, scholars believe that the earliest version of the Valmiki Ramayana dates from the 7th to 4th centuries BCE, with later stages extending into the 3rd century CE. During this period, the land was ruled by powerful, stable kingdoms.

Geopolitical Shifts and Cultural Impact

By the time the Ramayana was translated into regional languages in later periods, the geopolitical landscape had changed significantly. In the 11th century, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, from the Ghaznavid Empire, raided large parts of Gujarat and Punjab. The Muslim invasion of Bengal in 1202, led by Bakhtiyar Khalji, marked the furthest eastern expansion of the religion at the time. During the 14th century, the Khalji dynasty. Under Alauddin Khalji, pushed Muslim power further south to Gujarat, Rajasthan, and the Deccan. Additionally, Tamil Nadu was briefly incorporated into the new territory of the Tughlaq dynasty.

The atrocities committed during these invasions and conflicts were not confined to the battlefield; they extended to the cities, palaces, and rural areas as well. The invaders would engage in acts of violence, including raping women and killing men. In such tumultuous times. The prevailing culture likely believed that women would be safer and better protected by staying at home. It is possible that the poets of the era created the story of a boundary. That women were not supposed to cross as a reflection of this belief.

From Boundaries to Breakthroughs

Religious stories have long been a common method of teaching societal rules. To instill this rule equally in the minds of both men and women. The poets may have chosen to weave it into the narrative of Sita and Rama. As time passed, the geopolitical landscape continued to evolve. During British rule and later in independent India, women emerged in various fields. Including business, academia, art, politics, and public service.

For those who followed Rama’s journey from Ayodhya to Ayodhya through Panchavati and Lanka. The memory of the Lakshman Rekha lingered. However, it is now time to move beyond that notion and celebrate the significant contributions women. Have made toward a more prosperous and progressive society. This Women’s Day, let us honor the journey from mere survival to remarkable achievement!