Discovered over 150 years ago, La Tène lent its name to the second half of the Iron Age across much of Europe, with its distinctive artifacts often linked to the Celts. But what exactly was uncovered at La Tène? Andrew Fitzpatrick and Marc-Antoine Kaeser examine the evolving interpretations of this iconic site.

The Discovery of La Tène and Its Impact on Archaeology

The Archaeological Fever of the 1850s

In the 1850s, archaeology was booming in Switzerland. A particularly cold winter in 1854 led to an unusually low water level in Lake Zürich, revealing a Neolithic lakeside settlement at Meilen, abandoned over 4,000 years earlier due to rising water levels. This discovery ignited a widespread fascination with ancient settlements, leading to the identification of similar sites across Switzerland, Italy, France, and Germany. The artifacts found in these locations quickly became highly collectible, attracting tourists who could even walk on the wooden floors of prehistoric houses. The phenomenon, often referred to as ‘lake-dwelling fever,’ fueled a growing trade in antiquities.

The Discovery at La Tène

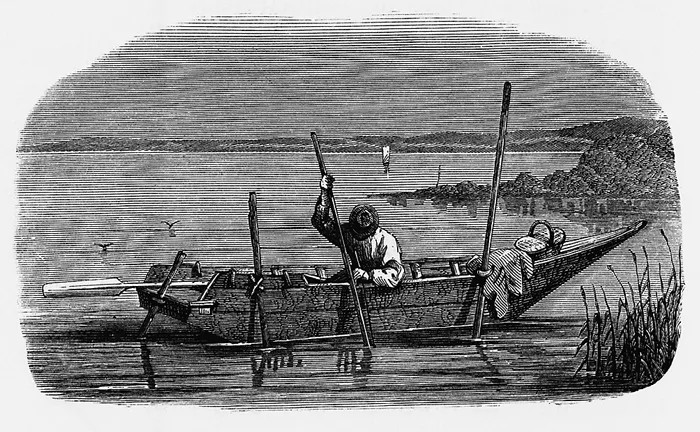

In November 1857, Hans Kopp set out to explore a settlement at Concise in Lake Neuchâtel. On his journey, he noticed some wooden timbers near the shore in a small bay called La Tène. Curiosity led him to investigate, and within an hour, he had recovered 40 objects, including 14 swords and eight spearheads. Unlike previous finds, which were predominantly bronze, all of these weapons were made of iron. This groundbreaking discovery was later dramatized in Louis Favre’s novel Le Robinson de La Tène, where Kopp remarked, “We have fallen on one of the most remarkable sites… bronze is completely absent.”

La Tène as a Type-Site

While Keller hesitated in his conclusions, another scholar, Édouard Desor, recognized the significance of the find. A geologist and palaeontologist, Desor was instrumental in developing the concept of the Ice Age and had connections with leading European archaeologists. Unlike Schwab, Desor was not focused on attributing artifacts to specific peoples like the Alemanni. Instead, he was interested in classifying objects within the emerging Three Age System (Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages), which had been pioneered in Denmark by Christian Thomsen.

By coincidence, Desor’s cook, Marie Kopp, was the sister of Hans Kopp. Through this connection, Desor learned of the La Tène finds and quickly hired Kopp to collect artifacts for him as well. Desor was convinced that La Tène represented a distinct phase of the Iron Age and could serve as its type-site. He published this interpretation in 1865 in a book on Swiss lake dwellings, which was later translated by the Smithsonian Institution to provide analogies for American archaeology.

La Tène Gains Global Recognition

Following its initial discovery, La Tène continued to yield artifacts. However, Desor soon turned his attention to broader archaeological endeavors, helping to establish the Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistorique in 1865, a forerunner to today’s Union Internationale des Sciences Pré- et Protohistoriques (UISPP). The 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris prominently featured Swiss lake-dwelling artifacts, including those from La Tène, exposing them to an international audience.

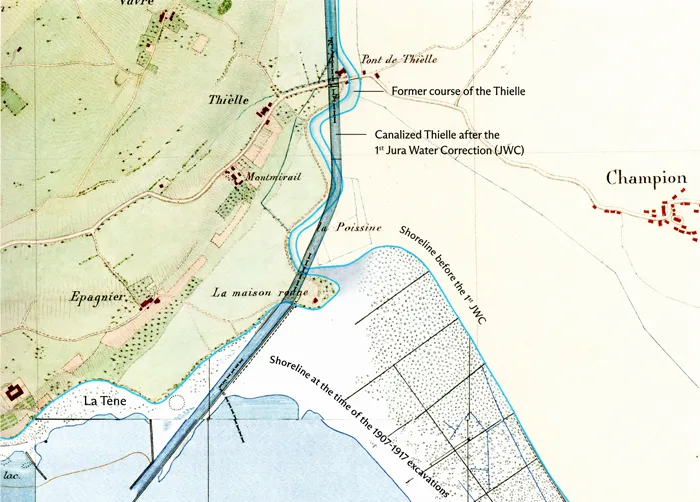

The Impact of the Jura Water Correction

By the late 1860s, Schwab believed that La Tène had been thoroughly excavated. However, the Jura Water Correction project (1868–1879) dramatically altered the landscape by deliberately lowering Lake Neuchâtel’s water level by nearly three meters. This exposed the La Tène site, allowing further exploration. Though much of this activity resembled treasure hunting rather than systematic archaeology. Artifacts from the site were sold to collectors across Europe and as far away as America. Further cementing La Tène’s status as a key Iron Age site.

Conclusion

The discovery of La Tène marked a turning point in European archaeology. It not only provided a wealth of Iron Age artifacts but also played a crucial role in refining the Three Age System and defining the later stage of the Iron Age. Today, La Tène remains a touchstone for scholars studying the Celts and early European history. Reflecting the lasting impact of a serendipitous discovery in a Swiss lake over 150 years ago.