Indigo Revolt

In the summer of 1859, thousands of ryots, or peasants, in Bengal refused to cultivate indigo for the European planters who owned the land and the dye-producing factories. This act demonstrated unwavering commitment and fury, marking one of the most notable peasant revolutions in Indian history. It came to be known as the Indigo Revolt or Neel Bidroha.

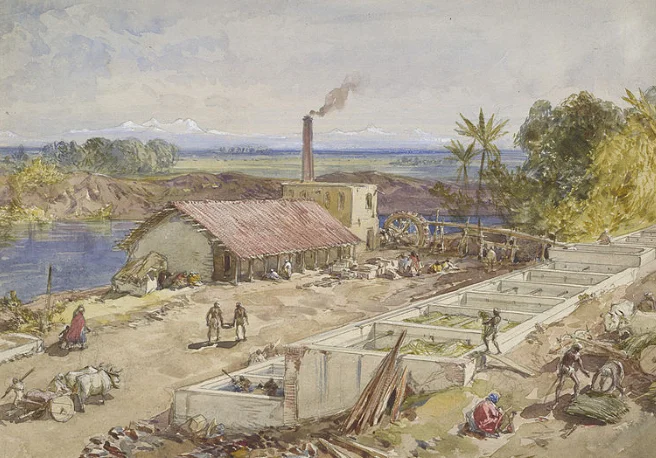

Since the end of the eighteenth century, Bengal has been cultivating indigo in two primary forms: the Ryoti and Nij-abad systems. Under the Nij system, also known as “own,” the planters themselves cultivated indigo on land directly under their control. In the Ryoti system, ryots cultivated indigo on their own fields under contracts with the planters.

The planters acquired land rights through various means. They obtained waste or vacant land from the Zamindars through either short-term or long-term leases. They also acquired rights to Taluqdari and Zamindari. Sometimes, indigo planting would also be practiced on the grounds of ryots who had either abandoned their communities or died without leaving an heir.

Ryots in Bengal

In Bengal, ryoti was the most common method of cultivating indigo. The ryots used a contract system for their indigo seeding. The contract covered a duration of one, three, five, or 10 years. At the beginning of the contract, the planter paid the ryot an advance to cover the costs of cultivation. The ryot committed to growing indigo on his property in exchange.

Usually, advances of two rupees per beegah were given in October or November. According to the contract, the ryot had to plant indigo on the land, weed it, and deliver it to the European planters’ indigo factory so that the plant could be processed into dye.

The accounts used to be written out in August or September, at the end of the production season. They included the cost of the contract’s stamp paper (two annas), the advance (usually two rupees per beegah), and the cost of four to five seed seers — charged at four annas per beegah — in the debit. The credit included the value of the indigo plant bundles that the ryot brought to the factories — typically four to eight bundles per rupee. A beegah typically yielded between 10 and 12 bunches.

Source: Old Indian Photos.

Farming seasons for ryots

The credit and debit amounts were balanced, and payment was made accordingly. If the ryot had a surplus or “fazil,” he was compensated. If not, he incurred a debt. Despite the debt, he received a new advance for the upcoming season. However, the ryot was given only the remaining amount for the next farming season, with the debt deducted from the entire advance payment. In some cases, if the debt was substantial, the ryot was compelled to cultivate indigo without receiving a new advance!

The exploitative nature of the indigo growing technique prompted the Bidroha to first appear in the Nadia area in 1859, and by the 1860s, they had spread to other Bengali districts. Peasants stormed the indigo manufacturers with spears and swords. They thrashed planters for making rent demands. Women engaged in combat with pots and pans as well. The Pabna area, where ryots refused to plant indigo, was particularly affected by this movement.

Source: Old Indian Photos.

Groups of people crowded the banks of the Kumar and Kaliganga rivers, pleading for a government decree prohibiting the growing of indigo, as observed by Lieutenant Governor of Bengal J.P. Grant. Women also gathered in groups to support the cause. Grant noted significant significance in this potent protest spanning a vast portion of the nation.

Indigo Farming Practice

In response to widespread dissatisfaction with the indigo farming practice, the British government established a commission in March 1860 to investigate the issues. The commission, known as the “Indigo Commission,” consisted of five members: Chandramohan Chatterjee representing the Zamindars, Rev. J. Sale representing Christian missionaries, W. F. Ferguson representing European planters, and W.S. Seton Karr and R. Temple representing the British government.

The Commission eventually submitted its findings in August 1860, after hearing the testimony of 134 witnesses, including planters, Christian missionaries, magistrates, Zamindars, and ryots.

The Commission concluded that the system of advancements, in particular, rendered the indigo farming system oppressive in character. Some entered into it voluntarily due to rent obligations and annual attendance at the Durga Puja event, while others endured suffering because their father or grandfather had accepted the advance, thus trapping them in a debt cycle. The son sows feeling culpable for his father’s debt.

Source: Old Indian Photos.

Christian missionary from Kapasdanga

F. Schurr, a Christian missionary from Kapasdanga, informed the Commission that he was unaware of any ryot who had voluntarily taken an advance. They had no choice but to produce indigo since they would not have been permitted to grow anything else.

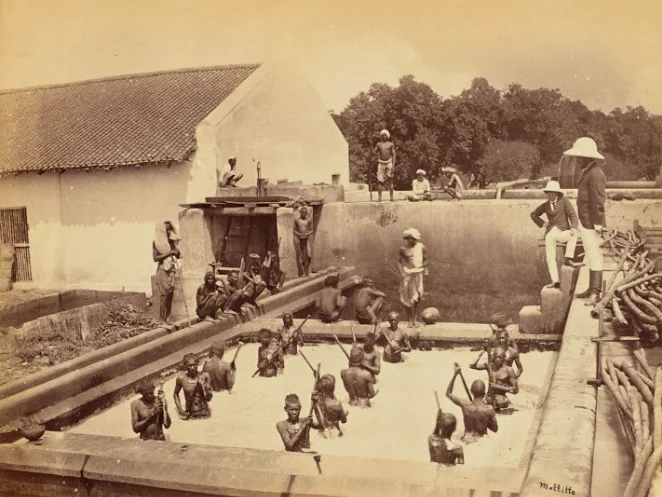

The manufacturing workers perceived the Bengali populace as “indolent, procrastinating, and faithless,” and thus they strictly supervised the agricultural activity. They subjected the ryots to what seemed more like “vexation and harassment.” The ryots protested that they were compelled to plow, break up clods, remove stalks, and repeatedly level the ground, to the extent that their work and time could no longer be considered their own. They endured constant humiliations to the point where they detested the moniker “indigo.”

The ryots grew to despise the crop due to its unprofitability. It was discovered that the ryots derived no profit from growing indigo, a fact even the planters could not dispute. “The cultivation is not popular because it’s not profitable, and the ryot has to bear the whole brunt of the risk,” stated one planter to the Commission.

Furthermore, ryots had little influence on the selection of lands. The planter determined which area of land would be planted with indigo; it was not put up for auction. The planter made his choice based solely on his desires.

Source: Old Indian Photos.

Barasat magistrate

According to Ashley Eden, the Barasat magistrate, indigo farmers were compelled to grow Indigo Revolt. He asserted that due to the unprofitable system and the harassment and violence they faced, ryots were coerced into submission.

The essence of the tyranny extended beyond economics. Landowners and their attendants used physical force on the ryots, rendering them completely helpless. Abadi Mundal, a ryot, recalled how one day, when his cattle were grazing on the plain, 50 or 60 latthials—men hired by landowners wielding lathis to intimidate ryots—arrived and started driving away his livestock. He suffered brutal assault and was taken captive for eight days when he tried to resist. “I still bear marks on my head and thigh from the injuries,” he said.

Another event recounted by F. Schurr involved a factory assistant who arrived at the rice field and demanded that all the rice be immediately transferred to the indigo field. A peasant requested the European assistant to wait until he completed his work, after which he would comply with the instructions. However, the European assistant responded with forceful strikes.

Source: Old Indian Photos.

Crimes

The Indigo Commission uncovered serious crimes such as robbing people of their rights, stealing animals, and clearing vegetation to make space for indigo. According to the Commission, whether the ryot had initially accepted his advance voluntarily or not made little difference; “he was never afterwards a free man.”

According to Ashley Eden, his district recorded 49 instances of murder, homicide, riot, arson, dacoity, looting, and kidnapping related to the cultivation of Indigo Revolt between 1839 and 1859. The Nadia presiding magistrate, W.J. Herschel, also submitted a report listing additional similar instances in Nadia.

The Indigo Planters Association urged the approval of Act XI of 1860, which made it illegal for ryots to “breach contract,” as many ryots had received advances and then refused to fulfill their obligations due to the exploitative nature of the contract system. With the assistance of this statute, the planters further oppressed and controlled the peasantry, bringing numerous lawsuits against them, particularly during the protest movement.

Source: Old Indian Photos.

Important Facts

The Commission concluded by recommending the following changes, stating that the relationship between the planter and the ryot was “unsatisfactory”:

1. The ryot should sow indigo according to his preferences and conditions.

2. The contract should be straightforward, lasting no more than a year, to prevent debt buildup, and there should be no renewal if the peasant did not fulfill his obligations.

3. Industries should bear the cost of stamp paper instead of ryots.

4. The choice of land for Indigo Revolt should be negotiated equally by all parties.

5. Industries, not ryots, should cover the transportation costs of the plant to them by boat or cart.

The Neel Bidroha

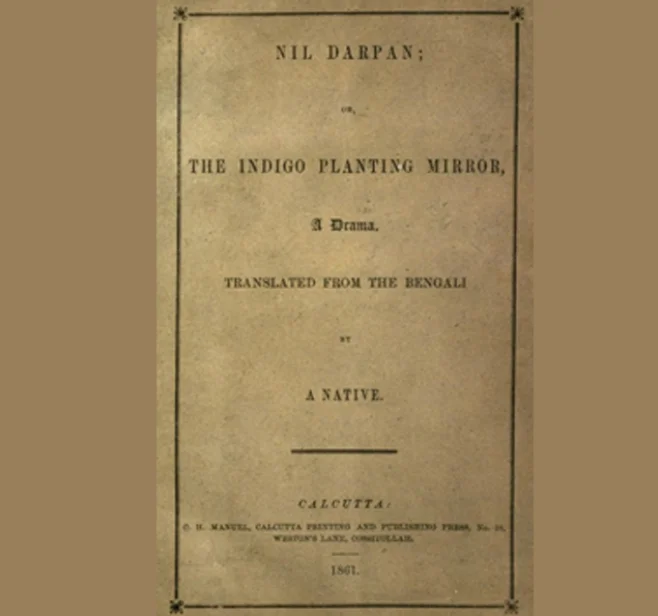

The Neel Bidroha influenced films, music, and literature. During the movement in 1859, Dinabandhu Mitra wrote the drama Nil Darpan, also known as the “Mirror of Indigo,” which continues to be regarded as a masterpiece. It depicted the hardships, persecution, and battles faced by Indigo Revolt farmers.

Despite enduring deprivation, subjugation, dominance, and humiliation, the Russian people did not allow their voices to fade. Throughout the entire process, their determination to refrain from planting indigo did not waver. This sentiment is aptly expressed in a quote from Panjee Mulla, one of the ryots: “I would rather be killed with bullets than sow indigo.”