Ellora Caves

Ellora lies around fifteen kilometers northwest of Aurangabad. The amazing cave temples in the hills, approximately one mile east of Ellora, have made it famous worldwide.

Once hidden from sight by the encroaching forest, these cave temples have become one of India’s most popular tourist attractions that few travelers are likely to miss. They are now formally involved on the World Heritage List by UNESCO.

The Sahyadri Hills’ sheer basalt cliffs house these caverns, which were hewn out over centuries. The 34 named rock-cut structures are comprised of Jaina caves 30 through 34.

Buddhist communities in caverns 1 through 12, and Brahminical structures in caves 13 to 29. Cave 16 houses the world’s largest monolithic rock monument, the Kailasa temple of Ellora.

The Kailasa temple is 300 feet in length and 175 feet wide, constructed out of a scarp that is more than 100 feet high. Unlike many other ancient rock constructions, this temple complex was constructed from top to bottom, not bottom to top.

Artisans completed the task using only a chisel and hammer, without using scaffolds. Due to its expansive excavation and magnificent design, this cave stands as the greatest example of Indian architecture.

Related Story of Ellora Caves

Medieval literature, some of it legendary, refers to this rock temple as the Manikeshwar cave temple. The queen Manikavati of the Kingdom of Elapura constructed the rock temple, which is why it bears this name.

Legend has it that a certain monarch of Alajapura (present-day Ellichpur in Amravati District, Maharashtra) suffered from an incurable disease due to a transgression in a past life.

On a hunting journey, the king made his way to Mahisamala (Mhai-samala near Ellora). Accompanying the king on his journey, the queen bowed to the god Ghrishneshwar and promised to build a temple in Shiva’s honor if the king recovered.

After taking a dip in the tank at Mahisamala, the king found himself fully recovered from the sickness. Filled with joy, the queen insisted that the king immediately begin building the temple, allowing her to fulfill her pledge.

She decided to hold off on eating until she saw the sikhara, the topmost feature of the temple. The monarch gave his approval, but no architect was willing to finish the temple so quickly.

In response to the challenge, Kokasa, a resident of Paithan, Aurangabad, promised the king that the queen would be able to visit the sikhara within a week.

Kokasa and his team began cutting the granite temple from the top down to free the royal pair from their predicament in less than a week. The temple was thereafter dubbed Manikeshwar in homage to the queen. And the king established Elapura, a town now known as Ellora.

Historical Advancements of Ellora Caves

The Rashtrakutas ruled the Deccan after toppling the earliest Western Chalukyas in the seventh century CE. References found in inscriptions belonging to the dynasty credit Rashtrakuta emperor Krishna I (757–72 A.D.) with the construction of the Kailasa temple.

Although initially titled Krishneshvara after the Rashtrakuta King, the temple was formerly called Kailasa. Scholars agree that it is impossible to attribute the creation of the Kailasa Temple at Ellora.

Other monolithic carvings of architectural shapes to the relatively short reign of a single monarch. Instead, labor likely continued under several consecutive rulers for over a century.

The Kailasa Temple of Ellora Caves

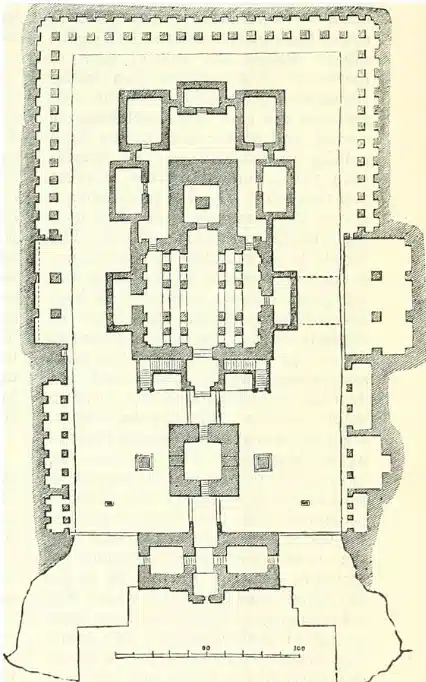

Scholarly discussions indicate that workers built the Kailasa temple by excavating three enormous ditches at right angles, digging vertically down to the base level of the hill.

This operation defined the perimeter of the courtyard while also leaving a sizable, isolated rock “island” in the center, which measured more than 200 feet in length, 100 feet at its widest point, measuring 100 feet in height.

An architectural assessment indicates that workers removed between 1.5 and 2 million cubic feet of rock through these tunnels. Scholars speculate that the sculptors chose the simplest approach, chipping the rock from top to bottom.

This method allowed supporting work crews to roll boulders removed from the area surrounding the main shrine down the mountainside. As lifting stones out of a trench that deep would have been nearly impossible.

It remains a mystery where the numerous tons of stones that were taken went. Furthermore, the workers would have needed to dispose of the rocks somewhere, but there is no proof that they stacked them up nearby.

Currently, we lack reliable sources regarding the whereabouts and purposes of these rocks.

Theories and Techniques Behind the Construction of the Kailasa Temple

Pseudoscience literature claims that locations such as Ellora have several secret tunnels beneath them that allegedly housed energy machines and other ancient technologies.

According to these claims, the massive Kailasa temple was constructed using these alleged alien devices. Mainstream discussions also mention legendary technology that purportedly could vaporize rocks. However, none of these theories are supported by trustworthy sources.

Art historians claim that humans in western India cut out numerous caves due to the natural chisel-responsive nature of the rock in this region. During exfoliation, the rock becomes softer layer by layer, revealing a firm core.

Sculptors and masons collaborated closely, with one team starting to carve details while the other team removed the rock. The artisans had ample space to sit and pound the stone with their elbows, eliminating the need for scaffolding because the caves were carved all the way around.

Construction Methods and Unanswered Questions

Scholars suggest that the architects had a working model and a pre-designed plan. Due to the striking similarities between Kailasa and the Virupaksha temple at Pattadakal.

It is widely believed that the same artists who constructed the latter may have also sculpted the former. Considering that the Kailasa temple is almost twice as big, it’s conceivable that the initial Chalukyan model was an inspiration.

But all we have are suppositions, and the actual construction procedure may have differed. The process of building raises several questions, especially considering that artisans used only a chisel and hammer to excavate such deep ditches and sculpt the granite masses in the center.

There is also no clear indication of how or where they disposed of the chiseled rocks. The awe remains at how ancient societies managed to achieve such a marvel, a feat that is challenging even with modern technology.

Kailasa and its architecture

At the entryway, a two-story Gopuram stands, adorned with gods sculpted on the sides of the doors, venerated by Shaivites and Vaishnavites. Two inner courtyards, each surrounded by an arcade with columns, can be viewed from the entryway.

In each courtyard on the north and south, there stands a single, enormous rock with a life-size elephant carved into it. The Rashtrakuta rulers, who revered elephants and believed in their efficacy in battle, may have commissioned these statues to symbolize their military prowess and wealth.

Upon reaching the great portico of Kailasa, guests encounter a carved image of Gajalakshmi seated atop a lotus. 4 elephants are seen in the surface: two smaller elephants fill jars with liquid from a lotus pool in the bottom row

And two bigger elephants sprinkling water in the top row water over Gajalakshmi from pots. According to legend, the panel promises wealth to any faithful devotee of Shiva.

Typical of Dravidian design, the sikhara (vimana) assumes an octagonal shape and rises 96 feet above the court beneath it. A modest antarala (antechamber) surrounds the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum), which connects to a sizable sabha-mandapa (hall supported by pillars).

In front, there is an agra-mandapa and on the sides, an ardha-mandapa. The shrine’s nandi-mandapa is carved between the gopura and agra-mandapa, with a rock bridge connecting the three sections.

The adhishtana, or platform, of the main temple features almost life-size sculptures of elephants that appear to be supporting the full weight of the building.

Artistic Depictions and Auxiliary Structures

Five auxiliary shrines line the circumambulatory route that hugs the hillside, honoring the Ganga, Jamuna, and Saraswati river goddesses.

Within the walls of the temple, two distinct 45-foot-tall kirti stambh (victory pillars) stand. These pillars no longer have the trisula that once decorated their capitals.

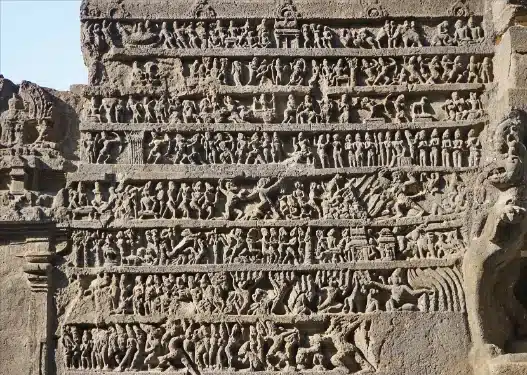

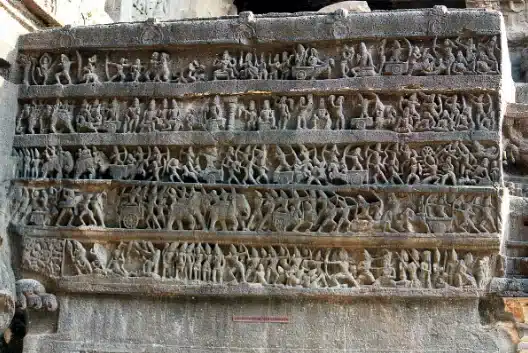

Behind the Dhwaja Stambha, two intriguing panels depict incidents from the Ramayana and Mahabharata on the outside wall flanking the main shrine.

The Ramayana panel consists of seven rows, each depicting a different scenario. It shows Rama leaving Ayodhya, Bharata attempting to convince him to return, scenes of Shurpanakha in the forest, Ravana kidnapping Sita, Rama meeting Hanuman. Hanuman crossing the ocean to reach Lanka, the Ashokavana, the scene in Ravana’s court, and, in the back row. The monkey army constructing a stone bridge to reach Lanka.

The Mahabharata Panel comprises ten rows. The bottom two rows depict Krishna’s early adventures, while the top five rows depict events from the Mahabharata battle, Arjuna’s penance, and the duel between Kirata and Arjuna as described in the Mahabharata.

Temple’s Name

According to a popular story, the Kailasa temple acquired its name because it once had a thick coating of white plaster that resembled the sacred Kailash mountain.

The temple is also known as the Rang Mahal, or painted palace, by scholars, implying that the entire building was once coated and painted.

Some remnants of ancient fresco murals can still be found on the porch roof of the higher temple. However, the extent to which the surface was painted white remains unclear.

An alternative interpretation considers the Kailasa temple as a metaphor for Kailash Mountain, believed to be Shiva’s abode.

The stunning three-dimensional sculpture of Ravana Anugraha Murti, located on the southern side of the main temple, is said to have inspired the name “Kailasa.”

In the murti, Shiva is depicted seated in repose, while Ravana is portrayed as a multi-armed figure attempting to lift Mount Kailash. The sculpture symbolizes Shiva’s ability to crush Ravana’s ego with just a slight pressure from his toe.

Behind the Temple

Apart from its stunning architectural characteristics, scholars interpret the temple complex’s layout as a journey from the physical to the spiritual, from the earthly realm to the heavens, and from matter to consciousness.

The gopuram, or entrance gate, serves as the primary point of entry, symbolizing the transition from the material world to the holy.

Moving from one mandapa to the next, artisans designed the hall’s dimensions, volume, and light to decrease, signifying a reduction in outside distractions and an increase in proximity to the divine realm.

Scholars believe that climbing the steps to the main shrine physically symbolizes a metaphorical ascent to heaven, with the towering, pointed sikhara acting as a representation of the celestial sphere.

Some scholars argue that the temple complex exemplifies the cohabitation of opposing components, which mutually support and legitimize each other’s existence.

For instance, the complete blackness of the caverns facilitates the appreciation of the sparse light filtering through the passages. The uncarved rock sides contextualize the finely carved areas of the complex.

According to another interpretation, a different group of scholars suggests that the Shiva linga located in the main shrine symbolizes the union of the diametrically opposed forces purusha and prakriti, representing creation and destruction.

Philosophical Symbolism and Structural Unity

Research has also explored the impact of Shankara’s advaita philosophy on the complex. Which includes a rocky hill carved with a deity, shrine, and devotee. This represents the integration of knowledge and devotion in non-dualism.

According to this philosophy, brahman, the ultimate principle of the universe. They believed to be the eternal universal spirit or consciousness underlying everything. Atman, the essential element of the human spirit and the essence of individual consciousness. It is considered to be independent and whole in itself.

In a similar vein, scholars perceive the components of the Kailasa Temple as complete entities in themselves. And their seamless interconnections create the impression that they form a unified complex.

Therefore, the entire Kailasa temple represents the Brahman and the universe, while each of its component pieces represents the Atman.

Resilience and Endurance of Kailasa Temple

Ellora’s Kailash temple embodies a harmonious blend of spiritualism and extraordinary architecture. It is widely acknowledged that no other Indian kingdom managed to construct a structure as magnificent as the Kailasa Temple at Ellora.

A smaller-scale effort by the Jainas to replicate such a feat resulted in an incomplete excavation known as Cave 30, referred to as Chhota Kailasa.

The temple was not only challenging to build but also deemed nearly indestructible. The Mughal emperor Aurangzeb purportedly attempted to demolish it to test its resilience.

According to medieval texts, this resulted in the destruction of most paintings and significant damage to sculptures. However, the caverns still endure.

ALSO READ: Maharaja Ranjit Singh also known as Sher-e-Panjab