Cave Temples of Mumbai

Cave Temples of Mumbai

Mumbai is home to historic cave temples honoring the Hindu and Buddhist religions. These caverns are located on the neighboring island of Elephanta, which is 11 km offshore, and on the island of Salsette (Shatshashthi), amidst some of the busiest suburbs of the capital.

Despite this, the caves remain silent. The three Buddhist caves of Mahakali, Kanheri, and Magathane, as well as the Hindu caves of Jogeshwari, Mandapeshwari, and Elephanta, are the most significant of the nearly 130 caves.

Source – Wikimedia Commons

Collectively, they narrate the history of the development of Buddhism and Hinduism, demonstrating how the Mahayana supplanted the Hinayana sect and how Hinduism converted caves into places of worship.

The Historic Cave Temples

Mumbai hosts historic cave temples that honor Hindu and Buddhist religions. These caves are located on Elephanta Island, 11 km offshore, and on Salsette Island (Shatshashthi), amidst some of the capital’s busiest suburbs.

Despite the surrounding hustle, the caves remain silent. Among the nearly 130 caves, the most significant are the three Buddhist caves of Mahakali, Kanheri, and Magathane, and the Hindu caves of Jogeshwari, Mandapeshwari, and Elephanta.

Collectively, these caves narrate the history of Buddhism and Hinduism’s development, showing how the Mahayana sect supplanted the Hinayana sect and how Hinduism converted these caves into places of worship.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Several of these caves were discovered during excavations on Salsette Island, which is located near the bustling ports of Chemula, Kalyan, and Sopara. Wealthy locals likely funded the excavation and maintenance of these temples and monasteries.

The island features hills with spurs extending westward to the sea, composed of uniformly layered horizontal trap-rocks with alternating layers of soft and hard rocks, ideal for carving and excavation.

Historic Caverns Through Centuries

Constructed over eight centuries, beginning in the first century B.C., these caverns served as hubs of worship. Before Ala-ud-din Khilji (1295–1316) overthrew the Devgiri Yadavs at the end of the 13th century, a succession of Hindu kings controlled the region.

The Muslim monarchs of Ahmedabad ruled the area until Portuguese settlers took over in 1534.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Around that time, several European explorers, including D’Orta, Linschoten, Fryer, Gemelli Careri, Anquetil, and Du Perron, explored and documented these caverns. Their convenient access from Bombay made this exploration possible.

In 1995, the city changed its name from Bombay to Mumbai. When appropriate, the article refers to the colonial metropolis by its historical name, Bombay.

Colonial Exploration and Preservation Efforts of Bombay’s Caverns

After the British East India Company took control of Bombay in 1668, English explorers began making trips to the caverns. Charles Boone, the English Governor of Bombay from 1715 to 1722, employed an Indian artist to create sketches of the Salsette Buddhist monasteries.

Which he then shipped back to England. Boone, along with Captain Pyke and Richard Bourchier, the Governor of Bombay from 1750 to 1760, provided detailed descriptions of these caverns.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Henry Salt and Major Atkins of the Bombay garrison included their drawings in his 1819 account of the caverns on the island of Salsette.

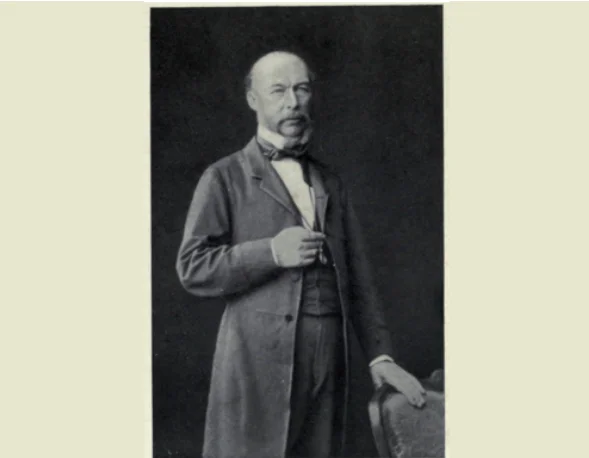

James Fergusson, an elected member of the Royal Asiatic Society, delivered a dissertation on India’s rock-cut temples to the Society in 1843.

This prompted the Society to write a Memorial to the East India Company’s Court of Directors, requesting efforts to document and preserve the caverns.

Consequently, the Directors instructed the Company to measure and depict the antiquities. In 1847, Dr. Bird reported his findings on the caverns, which sparked enough curiosity to establish a Cave Commission in Bombay in 1848.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological Surveys and Preservation Efforts in Western India

The Commission comprised Drs. J. Wilson, Stevenson, C. J. Erskine, Capt. Lynch, J. Harkness, Vinayak Gangadhar Shastri, and H. J. Carter. It operated until 1861, during which time it cleared the muck from the Elephanta Caves and received reports of artifacts.

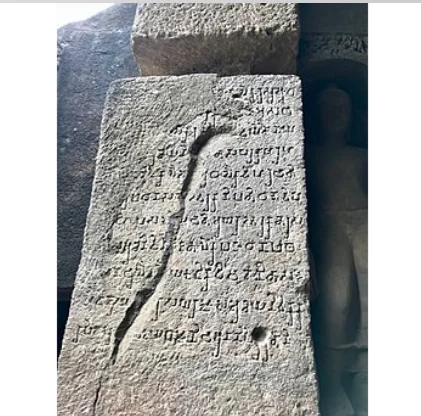

Dr. W. West and his brother, Mr. Arthur A. West, amassed a sizable collection of drawings and notes from the Bombay Presidency’s Rock-Temples. In July 1851, under the order of a dispatch from the Directors, they hired Lieutenant Brett to capture facsimiles of the inscriptions from the caverns.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1871, the Secretary of State for India in Council planned a study of Western India’s architectural antiquities. As a result, between 1871 and 1885, archaeologist James Burgess, who later served as Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India (1886–1899).

Head of the Archaeological Survey of Western India (1873), and of South India (1881), conducted a wide range of surveys throughout western India.

Advancements in Cave Architecture Research and Documentation

He provided his research and illustrations in three reports. The Secretary of State for India approved James Fergusson and James Burgess’ plan to write a comprehensive history of cave architecture in India in 1871.

Source: Archaeological Survey of India

A seminal moment in the study of these caves was marked in 1880 with the publication of their ground-breaking book, “Cave Temples of India.” Researchers kept looking for further records, translate inscriptions, and interpret numismatic discoveries.

Later, J. M. Campbell included a detailed description of the caverns in his Bombay Gazetteer. Campbell supplemented Henry Salt’s narration with his own eyewitness testimony, which served as the primary source for this portrayal.

Elephanta Caves

UNESCO designated the Elephanta caverns as a World Heritage site, making them the most well-known of these caves. These caves are located on Gharapuri Island, where the remnants of a stupa, monastery, and water cisterns indicate that the building was initiated by the Hinayana Buddhists in the second century B.C. However, no Buddha statues can be found there.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

During the following period (5th to 8th century A.D.), artisans constructed caves depicting the Hindu deity Shiva in various forms: as the three-headed God, Trimurti Sadashiva, Ardhnarishwar, Nataraj, and Yogishwara, along with several panels illustrating legendary tales associated with the deity.

Exploration and Discoveries at Elephanta Caves

In Cave 1, there exists a Linga temple with a circumambulation route. One of the earliest and most comprehensive accounts of the caverns came from the Portuguese explorer D’Orta.

The Portuguese named the island Elephanta after discovering a stone statue of an elephant near the landing spot. The monument’s dimensions were 7 feet, 4 inches high and 13 feet, 2 inches long.

Source: Archaeological Survey of India

In 1864, when the crane malfunctioned, the British attempted to transport the monument to England, but it fell and broke into pieces.

Sir George Birdwood, the curator of the Victoria and Albert Museum, now known as the Bhau Daji Lad Museum, assembled the monument at Mumbai’s Victoria Garden, presently Veer Jijamata Bhosale Udyan, where it is currently exhibited.

Portuguese Viceroy Dom Joao de Castro took a stone inscription near the caves to Portugal because he couldn’t find someone to translate it.

It was subsequently reported lost as even the King couldn’t decipher its contents, which may have provided insights into the time period and identities of the cavern’s architects.

Source: Archaeological Survey of India

Kanheri Caves

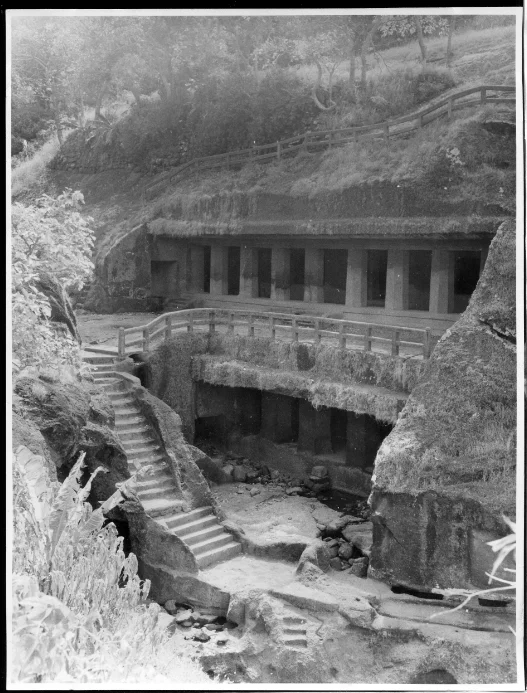

The Kanheri Caves were built between the first century B.C. by Buddhist monks. They are situated in the Borivali area and are currently a component of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park and the tenth century A.D.

They experienced the Buddhist periods of Hinayana and Mahayana throughout this extended time. As a result, the later caves feature elaborate reliefs and sculptures of Buddha and the Bodhisattvas.

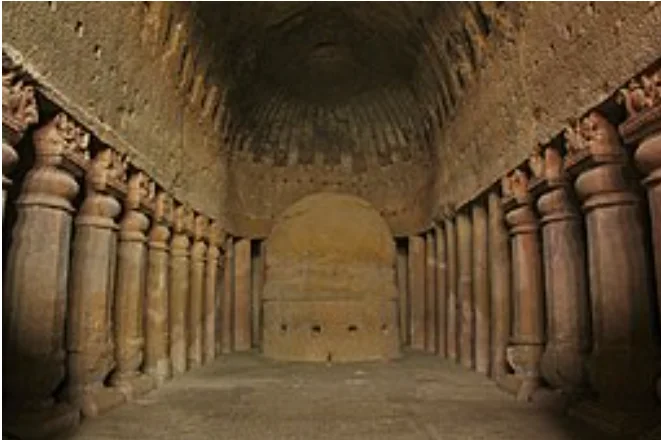

While the early caves are relatively plain and unadorned. Within the caverns, there are several Chaityas (prayer halls), Viharas (living quarters), and other utilitarian buildings, indicating that this was a sizable monastery and a center of study.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Cave No. 3’s huge Chaitya hall features a remarkable stone fence surrounding the outside courtyard. The dimensions of the hall are 39 feet 10 inches wide by 86.5 feet long. It is divided into the nave and two side aisles by a total of 34 pillars. Inside, there is a simple 16-foot-diameter stupa.

Researchers have found over a hundred inscriptions in the Kanheri caves, written in the Prakrit language using the Brahmi script. While their content is primarily devotional, they provide valuable insights into Indian culture and religious customs.

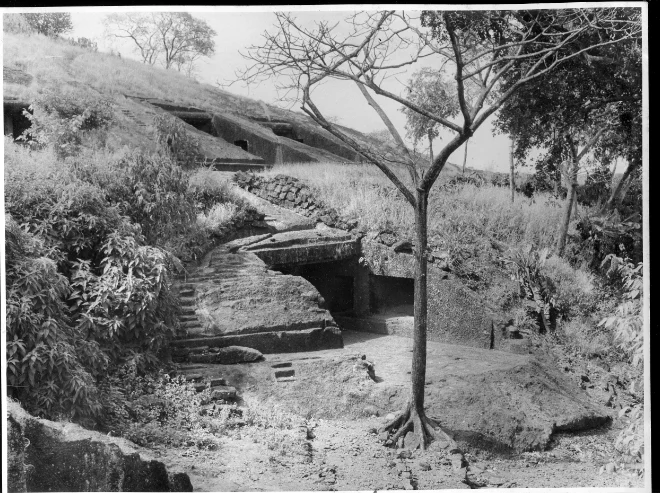

Jogeshwari Caves

These large Hindu caverns, constructed in the later part of the eighth century B.C., rank third in terms of majesty and decoration, only surpassed by Ellora and Elephanta caves.

Dr. Burgess asserts that due to its construction, there are no indications suggesting it was formerly a Buddhist monastery.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Instead, it appears to be the precursor to the structural temples that emerged in the eleventh and twelfth centuries A.D. in locations like Pattan Somnath in south Kathiawar (1198) and Ambarnath near Kalyan (1060).

The linga shrine occupies the center of the great hall, which is square-shaped rather than star-shaped like those at Elephanta and Ellora. Equidistant pillars divide the shrine from the aisles. Lord Shiva is depicted in the cave in both dancing and austere reclining positions.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Mahakali (Kondivte) Caves

The Mahakali or Kondivte caves are Buddhist caverns located in the contemporary neighborhood of Andheri. They were constructed between the second and sixth centuries.

Due to the friable nature of the rock, they are small—many of them are nothing more than cells—and heavily damaged. Two groups of caves are situated on the east and west faces of a hill.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The eastern row contains twelve caverns, while the western row has four smaller ones. These caves include prayer halls, residences, courtyards, and water cisterns. Sculptures of the Buddha and his companions adorn the walls, and a stupa is situated in the rear wall of the prayer hall.

Mandapeshvar Cave

In the Borivali area, the Mandapeshwar cave, also known by its Portuguese name, Montpezier or Monpacer, dedicates itself to Lord Shiva. In 1556, the Franciscan fathers transformed this spacious Brahmanical cave into a Catholic church.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

They constructed a wall in front of the cave and either plastered over or screened off the majority of the Shaiva sculptures. The church honored Nostra Senhora da Conceicao as its patron saint.

By command of the Infant Dom John III, King of Portugal, P. Antonio de Porto, a Franciscan missionary, also founded a sizable college here. The King intended the college to instruct all the natives who had converted to Christianity.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Additionally, the King granted the Church the earnings that belonged to the Hindu saints. The main hall measures 51 feet by 21 feet and features four ornate pillars in front. Two smaller rooms are situated at either end.

Behind a wall in the room on the left, large statues of dancing Shiva, Vishnu on his horse, Garuda, a three-headed Brahma, Ganapati, and Indra on his elephant are hidden.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Devotees and attendants flank these figures. The modest shrine chamber is located in the center of the rear wall. The monastery structure sits atop the low rock into which the cave is carved.

Magathane (Poinsar) Caves

In the contemporary Borivali district, there are Buddhist caverns housing a prayer hall and a monastery.

At the rear of the main cave’s hall, there is a large picture of the Buddha in the Gyana Mudra, with several smaller representations of the same posture arranged over his shoulders.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The walls of this temple feature several images of Buddha sitting on the Lotus Throne, supported by Naga figures, carved into them. Between the arched entryway, there is a decorative frieze adorned with two makara heads.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

According to reports from Henry Salt, there are cells outside the main cave. One of these cells features a large, highly relief-carved image of a sitting Buddha on its walls, accompanied by two attendant figures. The ruins indicate that the caverns date back to the sixth or seventh century A.D., despite their deteriorating state.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

ALSO READ: The Evolution of Parsi Theatre in Bombay