Darjeeling Himalayan Railways Engineering Marvels

Darjeeling Himalayan Railways

Travel: From Calcutta to Darjeeling in the 19th Century

Traveling from Calcutta to Darjeeling was difficult throughout the 19th century until the Northern Bengal State Railway expanded its service to Siliguri in 1879.

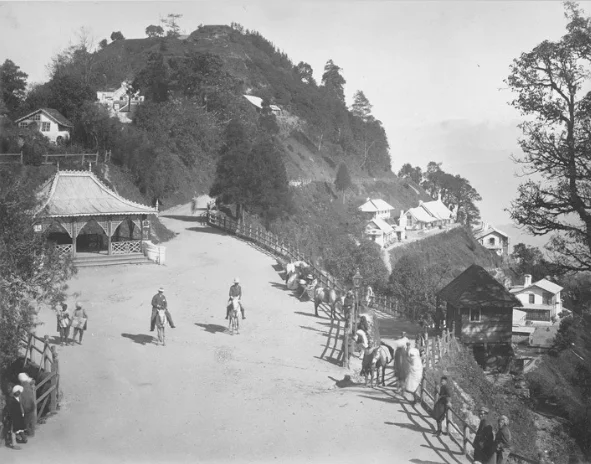

Travelers used various modes of transportation to reach Darjeeling, including the road, train, steam ferry, and bullock cart. The trip took five or six days. They relied on pack ponies, bullocks, palkees (palanquins), pony tongas (horse-drawn carriages), and bullock carts to navigate the Hill Cart Road. People viewed the railway as the solution to the transportation challenges posed by this road.

Now that required supplies, tea garden equipment, and troops could be brought to the hills in a timely manner, tea and other local produce from the Darjeeling hills could be readily transported to the lowlands.

After a continuous rail ride from Sara Ghat, travelers would have breakfast served to them in the morning at Siliguri, which is 400 feet above sea level in the foothills of the Himalayas. The trip would now take less than a day when travelers switched from a meter gauge system to one with rails spaced about two feet apart.

The Historic Journey of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railways

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway’s small trains covered the remaining distance. Passengers were astounded by its minuscule size, with tracks arranged like those in a package of toy trains.

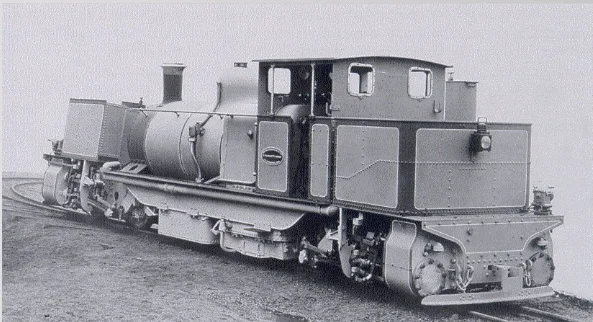

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, also known as the Toy Train, was a true technological marvel without its endearing features. It was built by engineers around 1879 and 1881.

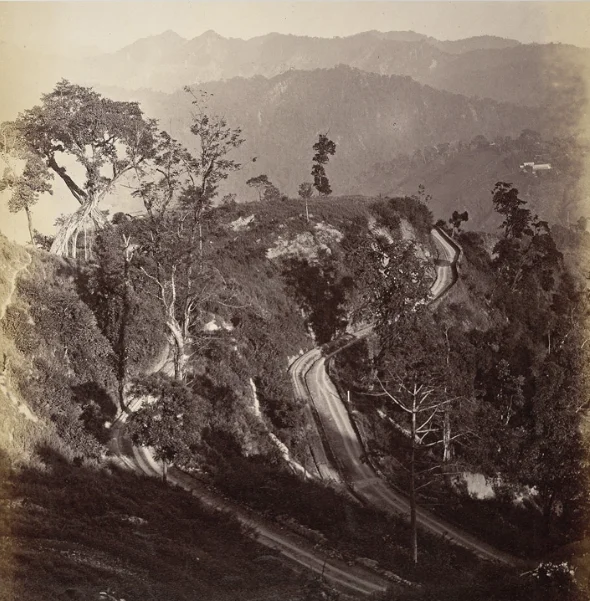

The construction of the Hill Cart Road, that started in 1839 by Lieutenant Napier of the Royal Corps of Engineers, is connected to the history of the Toy Train, who had been sent to plan the town of Darjeeling.

In 1835, British India annexed this small strip of mountainous country, previously part of the Kingdom of Sikkim. Due to the town’s expansion, officials deemed the Old Military route, formerly the cart route to the hill station, inadequate.

They authorized a new road in 1861. The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway gradually made its way from the foothills to Darjeeling, navigating several spurs along the way. This brand-new route linked Darjeeling with Siliguri.

Development and Evolution of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railways

Sir Franklin Prestage, an agent of the Eastern Bengal Railways, proposed the building of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railways in 1878. Sir Ashley Eden, the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal at the time, approved the plan and estimates in 1879 and submitted them to the Government of Bengal.

Subsequently, they developed plans to establish a business to carry out the endeavor and set aside Rs. 14,00,000 for this purpose. In 1879, Prestage founded the Darjeeling Steam Tramway Company, marking one of the first examples of a private initiative in the railroad industry.

However, under the conditions of a subsequent contract, he was compelled to reduce the line’s gauge to 2 feet, 610 millimeters. The company renamed itself as the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway firm in 1881, a name it used until 1948 when the newly established Indian state took over.

Growth and Development of the Himalayan Railways in Darjeeling

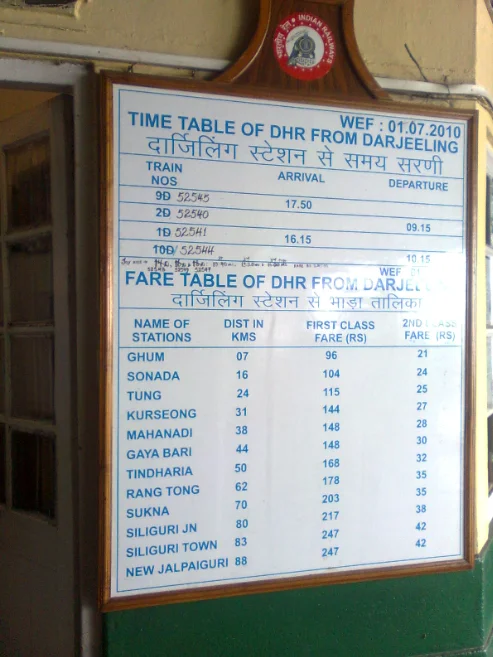

By August 1880, they had made the 32-mile route from Siliguri to Kurseong accessible for both passenger and freight traffic, located at 4,864 feet above sea level. After constructing 52 miles, they eventually inaugurated the entire route in July 1881 and reached Darjeeling Bazaar.

The construction cost totaled Rs. 31,96,000, averaging Rs. 60,400 per mile. The corporation made several preparations to ensure seamless service, including establishing maintenance facilities.

They modified the slopes of the line to facilitate the operation of large capacity engines. Glasgow-based Messrs. Sharpe, Stewart and Company manufactured the locomotives, and they installed solid steel tracks on timber sleepers.

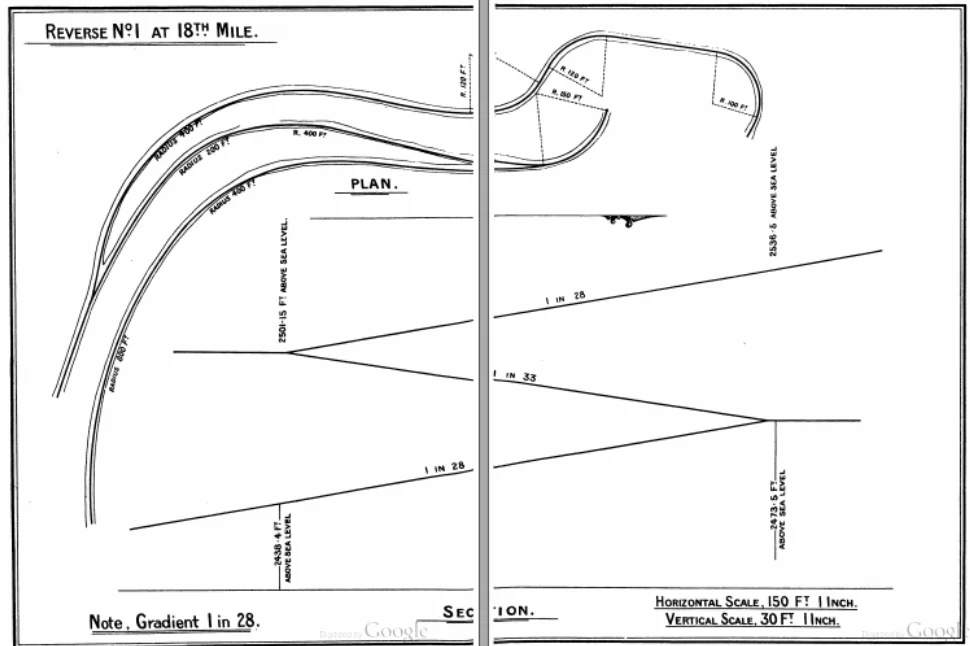

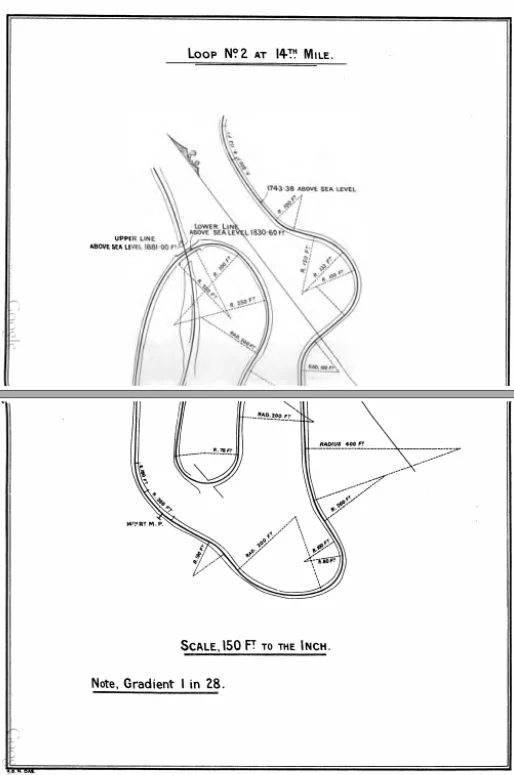

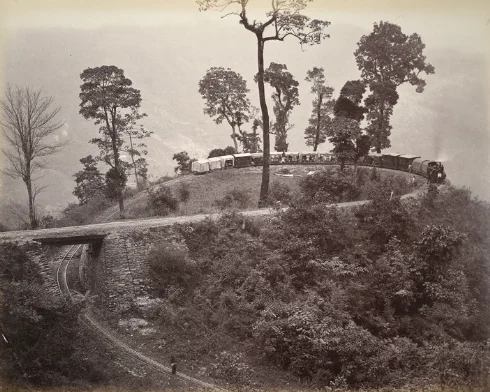

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway produced two different kinds of locomotives: one weighing about 12 tons capable of hauling 39 tons up steep inclines and around sharp mountain bends and curves and another weighing about 14 tons with strong brakes capable of pulling a 50-ton train up steep inclines. They had to build several loops, spirals, and reverses due to the high slope of the mountain to negotiate the route, necessitating extensive and expensive changes.

Passenger Classes and Scenic Travel on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railways

The train designated different carriages for carrying different passenger classes. The First Class passenger carriages had low floors, measuring 13 feet by 6 feet and rising 7.5 feet above the rails.

These carriages had two compartments and were equipped with 19.5-inch wheels. They could accommodate up to 12 passengers and small parcels that were stored beneath the seats.

Even though these carriages were ideal for rainy days, there was little opportunity for sightseeing. Each passenger train would attach an open trolley, capable of accommodating sixteen people in second class or six in first class. Passengers on these hooded and curtained trollies could enjoy the breathtaking scenery as the train wound its way up from the foothills.

Travel Tips for Darjeeling Himalayan Railways Passengers

The Eastern Bengal Railway encouraged travelers to pack additional clothes for the significant temperature swings and recommended waterproof gear from June to October, when there is heavy rain, in their brochure “Hints to Visitors.”

Travelers were advised to arrive at the station at least thirty minutes before the departure time. It was suggested to take a seat on the left side of the carriage on the way up to avoid the glaring afternoon heat, observe the plains, and prevent dizziness from the changing landscape of the hillside and the decreasing oxygen levels. Separate trucks were used for transporting luggage.

A Journey Through the DHR: Exploring the Early Route and Landmarks

A traveler’s trip on the DHR a century ago would have started with the planned railway route beginning on level terrain, spanning approximately seven miles from Siliguri.

The train would have first offered passengers a view of the Panchanai Tea Garden, the first tea garden they would encounter on their journey, after crossing the Mahanadi River on a 700-foot-long iron bridge.

The climb into the highlands would have commenced at Sukna Station, approximately seven miles from Siliguri.The travelers would encounter dense woodland, occasionally spotting elephants.

The line’s first steep turns would greet them at the ninth mile. This location was considered dangerous due to the high rate of malarial fever deaths among construction workers.

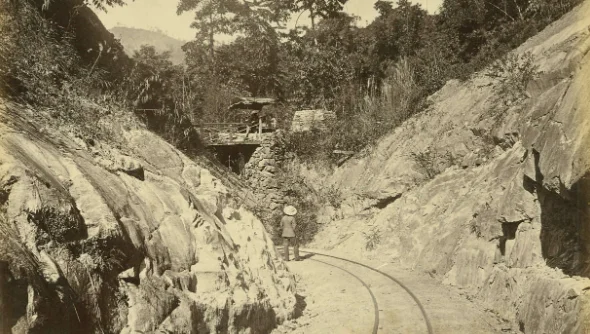

At eleven and a half miles, the route would encounter its first spiral, or loop, which was a defining characteristic. Engineers carried out an impressive engineering feat to allow the line to traverse the severe grades, including constructing the loop.

Exploring the Charming Twists and Turns of the DHR Route

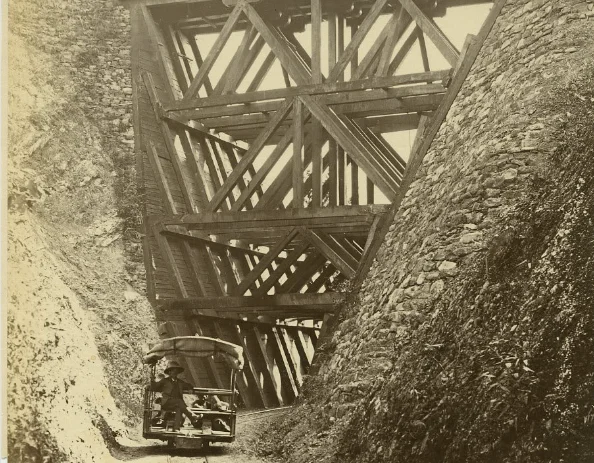

Between the twelfth and thirteenth miles, the train would stop at Rungtong Station to cool down and replenish water. The route curved north and east into the third loop at the sixteenth mile after heading south towards another spiral and crossing a gap resembling a tunnel.

Moving forward, the first set of reverses, known as the “zigzag” or reverse, appeared at the seventeenth and a half mile, marking another distinctive feature of the route.

Lily Ramsey, wife of Henry Ramsey, head contractor of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Developed this zigzag pattern as a technique for navigating the slopes. It was inspired by the backward and forward movements of ballroom dance.

The company located its locomotive workshops at the Tindharia stop. The second stop on the hill line at the twentieth mile. The line then proceeded to the fourth loop at Agony Point and another of the “zigzags.”

Exploring the Heights and Loops of the DHR Journey

Between Gayabari Station at mile twenty-third and twenty-fourth, the journey would encounter two additional “zigzags.” The midway point would be reached at Pagla Jhora, also known as “Mad Torrent,” situated at about 5,000 feet in elevation.

The train would then stop at the town of Kurseong. Continuing onward, the next stop would be Sonada Station, located at 6,552 feet. The train would proceed to Ghum Station, the highest point on the line at 7,407 feet in elevation.

From there, it would descend towards Darjeeling town. To manage the steep descent, the Batasia Loop was constructed in 1919, reducing the drop of 140 feet from Ghum to Darjeeling.

The train eventually stops at the Darjeeling terminal, giving passengers a much-needed break.

Today, the DHR route remains mostly unchanged, and passengers on this mountain train continue to travel in the same manner as their forebears.

Thus, one might say that the route serves as the sole link between the past and the present. Even though the scenery has changed significantly over the course of a century. And the DHR underwent a diesel heart transplant in 2000 with the introduction of NDM6 locomotives.

ALSO READ: Kabir Das: Bridging Hindu-Muslim Divide