Jallianwala Bagh

The slaughter at Jallianwala Bagh turned the tide in the Indian independence movement. In 1951, the Indian government erected a memorial in Jallianwala Bagh to honor the memory of the Indian revolutionaries and those who perished in the heinous slaughter.

It continues to inspire children with a sense of patriotism and serves as a symbol of sacrifice and effort. In March 2019, the Yaad-e-Jallian Museum opened its doors, presenting an accurate narrative of the massacre.

Political Circumstances

The massacre in April 1919 resulted from several unrelated causes coming together, rather than being an isolated event. To comprehend what happened on April 13, 1919, one must consider the preceding circumstances.

The Indian National Congress believed that self-governance would be granted after World War I, but the Imperial bureaucracy had different ideas.

Reason Behind the Jallianwala Bagh Bloodbath

On March 10, 1919, the government passed the Rowlatt Act (Black Act), giving it the power to detain or jail anybody suspected of engaging in seditious activity without a trial. This resulted in nationwide turmoil.

Gandhi started the Satyagraha movement to oppose the Rowlatt Act.

Gandhi wrote and published a piece titled “Satyagrahi,” outlining strategies for opposing the Rowlatt Act, on April 7, 1919.

British authorities conferred among themselves on the appropriate course of action to pursue against Gandhi and other activists involved in the Satyagraha.

They decided to prevent Gandhi from entering Punjab and arrest him if he ignored the instructions.

Sir Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab (1912–1919), recommended sending Gandhi to Burma, but his colleagues objected, fearing this would incite the populace.

In Amritsar, Drs. Saifuddin Kitchlew and Satyapal, well-known leaders representing Hindu-Muslim harmony, planned a nonviolent demonstration against the Rowlatt Act.

On April 9, 1919, while everyone celebrated Ram Naumi, O’Dwyer ordered Mr. Irving, the Deputy Commissioner, to detain Drs. Satyapal and Kitchlew.

This passage, taken from the November 19, 1919, Amrita Bazar Patrika, discusses Mr. Irving’s testimony before the Hunter Commission and sheds light on the British government’s perspective.

Deceptive Diplomacy: The Arrest of Dr. Kichlew and Dr. Satyapal

The Sir Michael O’Dwyer government ordered Irving to deport Dr. Kichlew and Satyapal. He knew this act would result in a public outcry. He also knew that neither of these well-liked politicians supported violence.

On the morning of April 10, he invited the two gentlemen to his residence, and they obligingly accepted, perhaps because they respected his honor as an Englishman.

However, after they spent thirty minutes as his guests beneath his house, he apprehended them and had them escorted by police to Dharmasala! Mr. Irving related this tale without displaying any indication that he had performed an act that not many Englishmen would choose to perform.

Enraged, the demonstrators marched to the Deputy Commissioner’s house on April 10, 1919, and demanded the release of their two leaders. The authorities shot at them without cause or justification, resulting in several fatalities and injuries.

The demonstrators assaulted any European who got in their path and replied with lathis and stones.

Contrasting Accounts: The Assault on Miss Sherwood

The crowd assaulted Miss Sherwood, the superintendent of Amritsar Mission School, on April 10, 1919. They stopped her and shouted, “Kill her, she is English” and “Victory to Gandhi, Victory to Kitchlew.”

They continued to assault her until she lost consciousness. Assuming she was dead, they left. ‘Lokasangraha’, a Bombay-based weekly, disputed the allegations of serious injury and asserted that the injuries were actually minor.

APRIL 13, 1919 – JALLIANWALA BAGH Bloodbath

After enacting the Rowlatt Act, the Punjab Government aimed to crush any dissent.

According to the British perspective found in the National Archives of India, the public had assembled to celebrate Baisakhi on April 13, 1919, but it was considered a political assembly.

Despite General Dyer’s orders against illegal assembly, people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh to debate two resolutions: one calling for the government to release their leaders and condemning the firing on April 10.

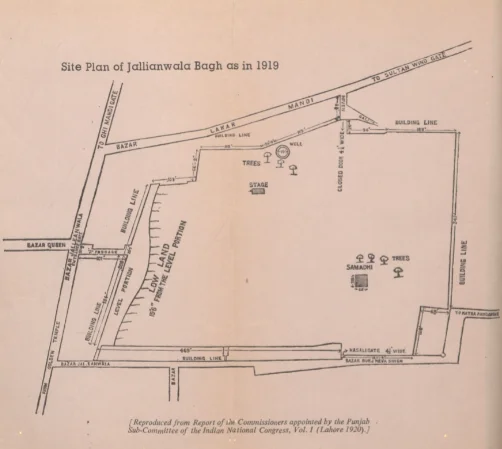

Upon receiving the news, Brigadier-General Dyer proceeded to the Bagh with his soldiers. Without warning, he ordered his forces to open fire as soon as he entered the Bagh. While many rushed to the exits, Dyer continued ordering his forces to fire.

The gunfire continued for ten to fifteen minutes, during which a total of 1650 shots were fired. The firing only ceased when the ammunition ran out.

According to estimates provided by Mr. Irving and General Dyer, there were 291 fatalities in total. However, some reports, such as one from a commission led by Madan Mohan Malviya, estimated the death toll to be over 500.

POST JALLIANWALA BAGH

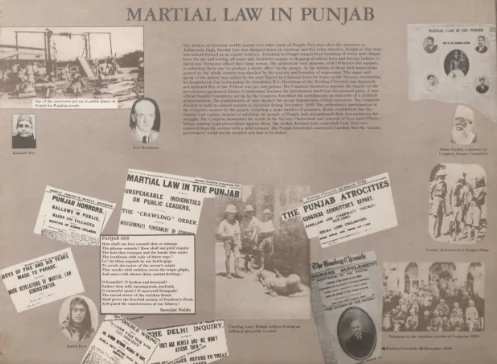

Two days after the slaughter, the authorities imposed Martial Law in five districts: Lahore, Amritsar, Gujranwala, Gujarat, and Lyallpore. The Viceroy was granted the authority to immediately order a court-martial for anyone suspected of participating in revolutionary activities upon the declaration of martial law. In response to the country learning of the massacre, Tagore renounced his knighthood.

HUNTER COMMISSION

The Disorders Inquiry Committee established on October 14, 1919, aimed to investigate the killings. It eventually became known as the Hunter Commission.

The Hunter Commission was tasked with assessing the government’s actions and justifying them, if possible. It questioned General Dyer, Mr. Irving, and all other British officials involved in the Amritsar unrest.

Here’s General Dyer’s callous response during questioning:

Question: Did you take any action to tend to the injured after the shooting?

Answer: No, I did not. I believed it was not my responsibility. They should have gone to the hospitals, which were open.

Sir Michael O’Dwyer promptly acknowledged General Dyer’s conduct on the day of the Massacre by sending him a cable message stating, “Your action is correct.

The lieutenant governor agrees.” Numerous publications that published their own versions of the horrific carnage harshly criticized both Dyer and Dwyer.

General Dyer’s testimony before the Hunter Committee amounted to an admission of the heinous deed he had perpetrated.

The Committee categorized the massacre as one of the British Administration’s worst moments.

Dyer received a rebuke for his behavior in 1920 from the Hunter Commission. Montagu’s letter to the Commander-in-Chief instructed Brigadier-General Dyer to resign from his position as Brigade Commander and conveyed that he would not be employed in India in the future.

O’ DWYER’S ASSASSINATION

Udham Singh, an Indian freedom fighter, assassinated Michael O’Dwyer, who had authorized Dyer’s operation and was believed to be the primary instigator, at Caxton Hall in London on March 13, 1940.

Gandhi condemned Udham Singh’s actions as an “act of insanity” and disavowed them. “We have no desire for revenge,” he added. “Our aim is to reform the system that gave rise to Dyer.”

It exposed a profound flaw in the latter’s attitudes and assumptions. Ultimately, they had to depart from the country they had intended to govern for generations as a consequence of it.